Halfway through Seemabaddha, Ray does something that surprised me pleasantly. He introduces a certain Mr. Ramalingam, a soon-to-be retiree at Peters’ Fans. He meets Shyamal, our protagonist, and speaks of something precious to be shown. Ushered into his office, the elderly gentleman takes out an old letter – as old as Shyamal himself – and dictates its contents, which he states were sent to him by his father when he joined the firm. The saying itself – one that warns of surplus ambition – invites a flush smile: it is a tactful modification of Thiruvalluvar’s Kural 691. Simply put, it states that if one resides too far away from the fire, he fails to benefit from it. If too near, he runs the risk of burns. The fire in question is to be the British, whereas the ambitious benefactor is Shyamal. “One cannot move ahead without that, Mr. Ramalingam,” is Shyamal’s response, to which the old man acquiesces. Plucking another branch from his tree of wisdom, he quotes Conrad this time; the only unlawful ambition, he orates, is the one that builds on the mound of human miseries. Departing with no wisdom of his own to declare, he leaves Shyamal right before disaster strikes.

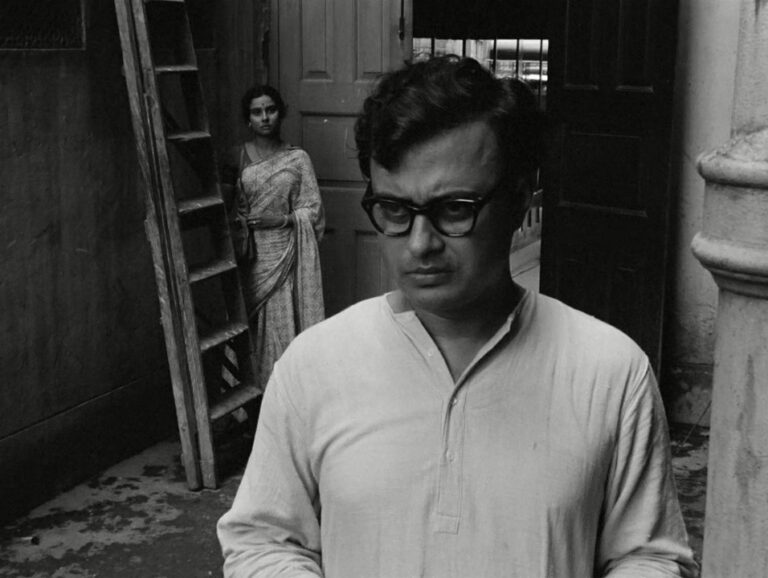

What pleases me? Apart from his choice to include a sagely Tamil saying, the scene recapitulates Seemabaddha itself, and more so, the two other constituents of his Calcutta trilogy. The one who exists too far away from a similar fire does so after recoiling violently upon first contact in Pratidwandi. The one who gets too near is handcuffed until he is branded in Jana Aranya. The one who exists, and vacillates, between the two states is Shyamalendu Chatterjee. Sprightly gait, slickly-combed hair, tongue-in-cheek remarks – he’s been left untouched by the gyrations of Calcutta. He marries his wife in Patna, where he lands his first job at Peters’ Fans. Making his fortunes and playing his cards to arrive at the port city unscathed, he lives in a house sat floors above the fraught airs of the ground. He even acknowledges his fortune at the start of the film through a voiceover. Ray’s film is then, in contrast to the two other films, about an ordinary Bengali who made his career away from the unordinary circumstances of Bengal. Fittingly, it’s sat like a dogged fly on the walls of post-independence corporatism, witnessing the absurdities of a new Indian elite who, years after the departure of the British, flounder with the predecessor’s crutch for their identity.

This flounder is made most prominent in the film’s establishing act – rhythmically and tonally. Until Ray establishes the gist of the film through Shyamal’s voiceover, the scenes move like a staccato. Flashes, gimmicks, hints of color – it’s all “snappy” as the ad producers note. On the other hand, the tonal misalignment with the later parts of the film – which I’m half-sure is a desired effect – manifests as a swipe at the contrived mannerisms of the office milieu. Half-hearted comments on hairstyles, the unusual French expressions, and Sir Baren Roy’s (Ray didn’t spare him the caricature-ish knighthood) cackles are all dialed up a degree to show how the new upper-class poached beliefs and modes of life as markers of status. “You see,” Ray recounted to Sight and Sound in 73’, “in a sense, the British have not really left.” Though today we speak of a post-colonial hangover, Ray was – largely due to his own Western predisposition – presciently aware of how we, in the pursuit of urban dreams, stuffed ourselves with new leftovers to recompense for what had been eviscerated over the last 200 years. Not that all of those beliefs were wrong. Some aided us to rid ourselves of social ills, some regimented or repackaged divisions, but largely, they cleaved and spliced a new identity.

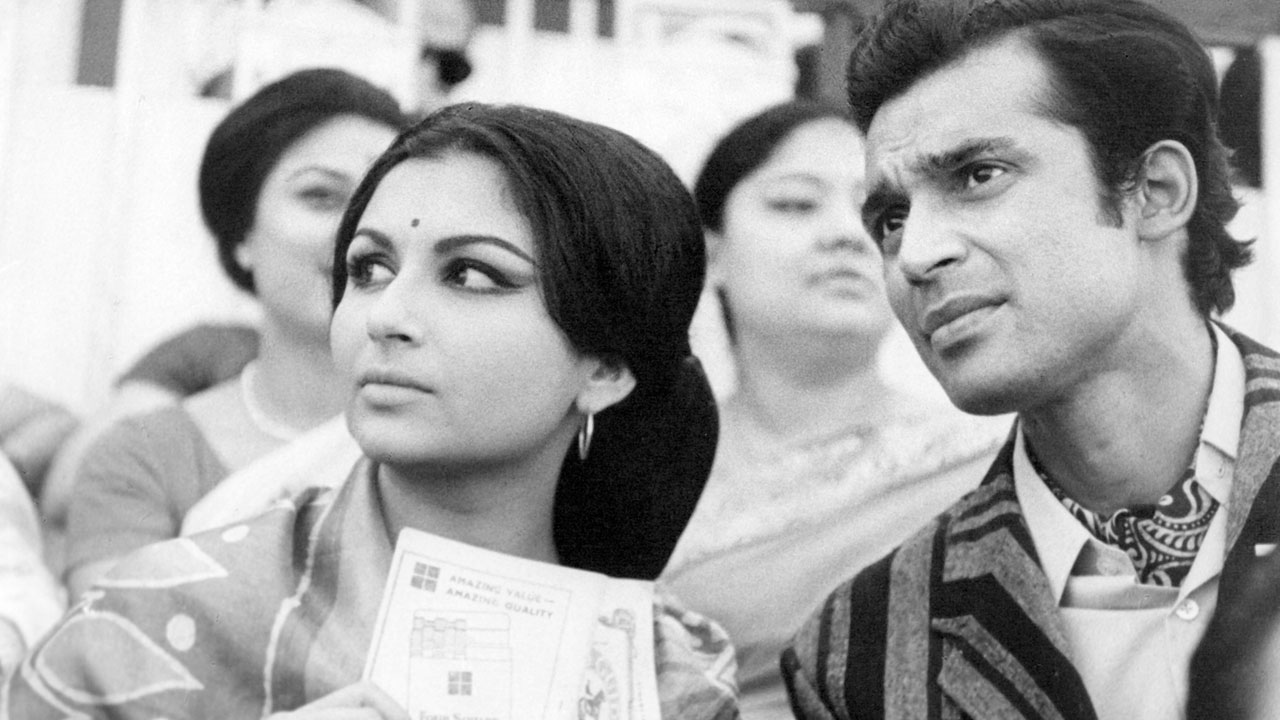

However, there’s a bridge that mitigates the tonal off-notes when they re-occur. Tutul, the Patna sister-in-law arrives and with her, she brings a gaze from the world that is remotely observant – true to her professional background as a psychologist – and smilingly judgmental – the result of her still-conservative household. As soon as she’s enmeshed in the narrative, Shyamal’s life is oddly different, even in her absence. By introducing her, and her off-beat comportment, Ray primes us to see his life in the way she does. When they go to the races, her eyes rapidly inspect the retinue and their comportment. Shyamal offers her his sunglasses, and she wears them (much credit to Sharmila Tagore for this) in a way that is elegant yet unbecoming of her own mien. So, having placed one against another, the wantaway escapee and the visiting home-bird, much of the film’s tension – and its joyful wordplay (as when Shyamal, stunned by his sister-in-law’s beauty, negotiates grounds of divorce with his wife) – prepare it for the precipitous turn.

Between this dynamic, there are two important anchoring scenes in the film. Let me address the first and lesser of these two: the juxtaposed La Dolce Vita party scene at Shyamal’s house, with men and women speaking of affairs and unemployment as if they were petty turbulences beneath them. Ray’s perspective is, nonetheless, more intimate than Fellini’s – the framing and sizing of his shots are much closer to the characters. Tutul, sat amongst smoke and silence, is visibly perturbed by their feigned anger and boisterousness – after all, as Shyamal recounts at the start, they are not, fortunately, “out of work.” When Shyamal’s parents arrive unexpectedly, Ray inserts the only multi-person shot as they cross the room. The execs and directors are unmoved by the new presence amongst them as he and his wife quickly aim to placate both parties by steering his parents into the bedroom. Tutul quickly follows suit to relieve them of their double-act, allowing them to return to their current role in these “higher” circles.

The lynchpin scene arrives as the night’s clinking glasses fade into dawn’s cleansing air. Shyamal and Tutul are up-early, and the windows have been thrown open to allow some city noise to percolate the room. Tea has been served and they both sit beside each other. He recounts how in life, as in school, one continues to do subjects that one doesn’t like doing – or else one “stagnates.” She doesn’t respond, and moves to the other side of the room, speaking of books and untidiness. He’s adamant on the subject of not attending unessential parties as long as she’s with them – another foray to play the double-act. The camera pulls out and they are both blocked into two parts of the room; she laments the loss of his qualities, his glasses, his other half that he’s desperately trying to project. “Is that good or bad?”, he surreptitiously implores; here, Ray intercuts as he looks at her brazenly, almost desiring. The sitar and clarinet that she started play witness to her uneasiness – more precisely to her fear that an answer would make him choose one state of existence at a very dear cost. He again moves closer to her and says that this morning the very same sitar and clarinet felt more appealing than golf with his superiors. The subtext evolves with such frightful care and tact (this could have very easily painted him in a much worse light) that Ray earns and re-earns his spot amongst the medium’s greatest.

This dedication to the smaller, yet protracted moments – or commonplace, as Kael calls them – is such a consistent feature of what makes me adore Ray’s cinema. Having pored over the archives these recent months, if I were to put my finger on a moment that shaped his cinema, I’d put it on his meeting with Tagore at Santiniketan. I can imagine a young Ray, handheld by his mother, walking into Tagore’s room. He places a cream-white notebook, freshly bought to register ideas, and places it before the great Bengali as his mother asks for something to be written for his son. Arriving the next day, Tagore hands him the notebook and says he’d come to understand what’s written much later. Inside it were these verses :

I have travelled all round the world to see the rivers and the mountains, and I’ve spent a lot of money. I have gone to great lengths, I have seen everything, but I forgot to see just outside my house a dewdrop on a little blade of grass, a dewdrop which reflects in its convexity the whole universe around you.

Fascinating, isn’t it? It’s almost as if Tagore reaches within you and yanks out all pretexts for being unappreciative of your immediate surroundings. But it’s that word – convexity – that I believe dropped very deep in Ray’s juvenile and impressionable mind. The one frame that speaks of a world, be it Apu staring at the train of progress tearing through fecund fields, Durga glumly staring at the marital ceremonies of her friend, or Charu swirling her binoculars to look at Amal while she’s sat on the swing, all speak of each film’s ineffable thematic pillars. Change, paucity, and solitude are wrapped not in a convex dewdrop, but a stretched-out frame with four corners. He has made us re-evaluate the commonplace, and in it, find stray shards of ourselves that have hitherto been clouded. Ray took that idea and drove it to its extremes – as he does in Seemabaddha – and for this, I shall appropriate and rephrase to call him the Lord of Small Things.

When the film’s final tide recedes, Shyamal returns home to an out-of-order elevator. Pacing the stares, he arrives to announce the news of his hard-earned promotion. His wife is over the moon, already counting the lakh and twenty in annual income (I find it a tinge funny that in all the elation, there’s hardly a mention of their son, who is pulled out of the darkness only for a prefatory mention). But Shyamal wishes to see Tutul, and when he informs her, she solemnly removes her watch, aware of how the promotion has transpired. In doing so, she answers his earlier question. As much as one desires, one cannot live with two separate consciences. The pipe-in-the-mouth insouciance and the behind-the-door obeisance can perhaps be yearned for – as one does when reading novels about the charming Janus – but not be practiced. It becomes too weary to uphold, and it does snap. But as the sagely Mr. Ramalingam says, “What has to happen can’t be uttered, it needs to be felt.” Words – as they never do in Ray’s films – don’t precipitate change; the silent dewdrops of subtext, the unseen, will.