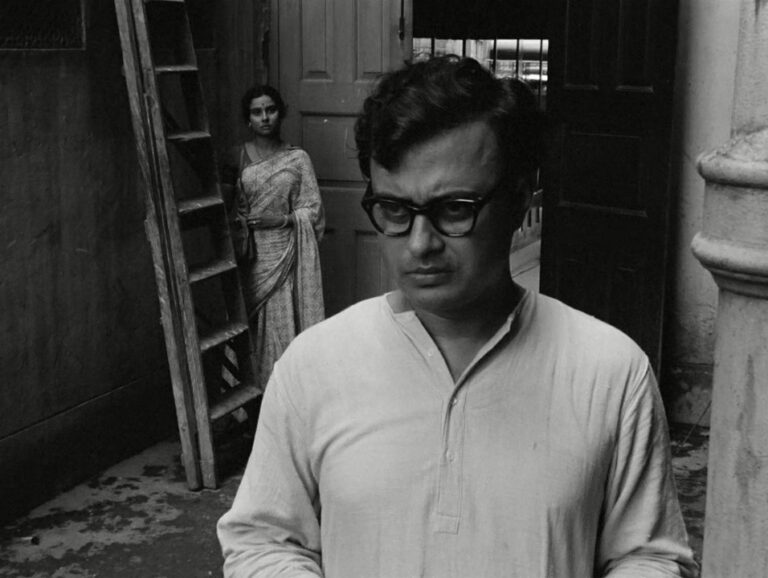

“I’ve heard that booksellers don’t read the books they sell,” tells Biswanath Bose, mouth-stuffed with a banana. “Do you ever eat your own bananas?”, he asks the squatting banana seller. The man smiles an uneasy smile – did he understand the question or was he surprised at an observation that he failed to make each day? Jana Aranya (an apt title when parsed – Jana meaning people and Aranya meaning forests) follows people – in their millions – droning through the forest of Calcutta like ants seeking to forage or apply themselves. They buy and sell duplicating papers, envelopes, dilapidated British mansions, and if an opportunity knocks, an elephant too. If scorched slowly by circumstances, they’d even sell you a prostitute. But would they ever use what they sell? They lavish adjectives – the finest, the strongest, the most durable, and the most beautiful. How much of that is the truth and how much of that is a hand itching to do away with the muck from scraping? Termed as the most cynical hour of Ray, the film isn’t so much critical of the transactional ways of our society for we cannot function without exchange. However, if pressed against the wall, how willing would we be to pass on items of no worth, or worse still, pervert their holistic value to crude denominations? “My name is Juthika,” Kauna spits out at Somnath, who, having fallen deep into the reductionist, single-value world, fails to realize that all that matters is what glitters.

Unlike most of the films that chart an industrial downturn, Jana Aranya isn’t a tirade on the external actors. There is no “they” and “us” – both refer to the malevolent and benevolent presences within us. As a result, the film isn’t a stack of dominoes that fall flatter and harder with each push; Somnath, the bright pupil, has a choice at every turn and his decisions fall either way. “Keep it,” he insists mockingly as he refers to the handkerchief after being jilted, “you might feel like crying again on the bus.” He doesn’t belie signs of vitriol. Instead, he even quips about having his whole life ahead of him. It’s been an entire day of downturns, yet he still doesn’t tip over. Later in the film, he smilingly listens to Mr.Mittir say, “I don’t consider myself dishonest,” seeking moral extenuations for the decision he is to grudgingly make. There are no empty bullets to bite, and he searches for cushions to soften the blow. By keeping the film as such and reinforcing the idea that we are all willing participants in the world that we have created, engaging in the choices that it presents us, Ray takes away the world-against-man trope and places a bleak mirror – increasingly spotty and dim with each turn.

What’s interesting is that the construct of the film would be fairly easy to spot for anyone aware of the three-act structure. There’s an inciting incident, conflict, and an imminent resolution. Now, all films adhere to this structure – but with many partitions and sub-partitions, each having crests and troughs. In this particular context, however, you could either spend a long time partitioning the cause or the conflict, and if warranted, the resolution too. Ray places his lens the longest between the latter two. We see Somnath learn the ropes of being a dalaal – a term he abhors but embraces, unbeknownst to himself. There’s the murky office with its crop of characters and each is eager to let him in on trade secrets; after all, they are grooming an asset. Ray is persistent in showing us this young upstart with a wiry frame making his way through Calcutta, be it on pulled carts or taxis, labouring to make the only living available to him. Being this man isn’t a quick way to riches, despite the prepositioned lucrativeness. It’s hard labour and it has its rewards, but when they are momentous, you either recoil or walk into an immoral trapdoor. By playing alongside this notion of perfect careers and prolonging the one moment of tension into hours and days, Ray displays the bilious underbelly of a career that we’d otherwise see as effort-reward commensurate. The whole film, then, is a set-up to the moment that we fear and sadly disregard the most – a seat across the table with Mephistopheles.

Given the ripe potential to showcase this as a dog-eat-dog world, Ray actively chooses not to. That choice alone lends the film a new perspective – one that reinstates agency. Somnath has his brothers and fathers in the trade that are all too eager to help him. It sounds too good to be true, doesn’t it? “Count what you get, and count what you give,” says one of them to an eager Somnath who pockets his first commission. Perplexed, he listens to him say that people are always looking for a chance to cheat, including himself. But isn’t that oddly counter-intuitive? It paints these middlemen like a pack of wolves – they’d only eat their own kind as a last resort. So, this current of support sweeps out all obstacles of conflict, and the few stray scenes with Sukumar only serve as gentle reminders to the protagonist and to us that there’s still more to his life than he chooses to think of with his new profession. These brothers and fathers egg him on to keep taking more bites, even offering it on a plate to him by rifling through their networks. Like a passage of rites, they draw him out to the last test to see if, should the circumstance arise, he’d not eat their hands – as established by the subtextual agreement. He doesn’t, and the steam of empty progress can scuttle ahead.

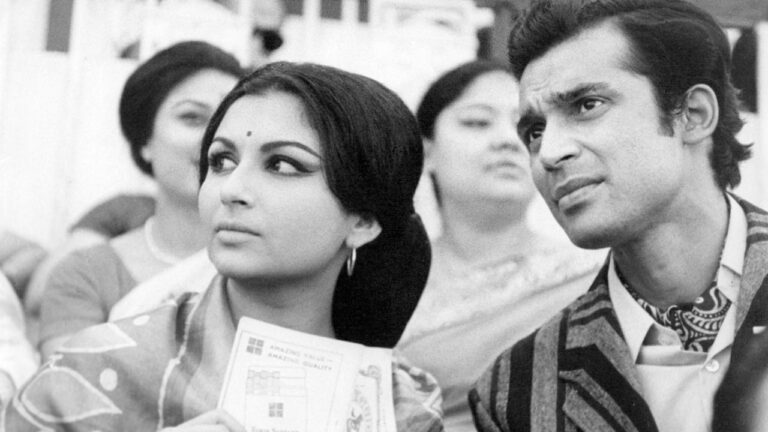

Throughout the three films that make up his Calcutta Trilogy, all of Ray’s characters have a growing sense of their own appearance in society and this culminates in Jana Aranya. Perhaps, the best example of this is in the final leg of the film, as Mitter and Somnath frantically search for a prostitute that fits the bill. Sat in the back of the car, Somnath listens to Mitter speak about his family and the education that he’s providing for his son. “I don’t have any hypocrisy or snobbery in me,” he says gleefully, “I get along with all kinds of people on equal terms.” He’s comfortable switching in and out of social roles – as long as they benefit him. It reflects the hyper-appearancist world that was taking root then (and which has fully formed now) that acts as a smoothened surface for the base acts beneath. As they run down the stairs after being shooed away by a prostitute’s husband, Mitter’s remark sums it all up – “Drives his wife to do it, now puts on airs and graces.” We feel a deep need to maintain morality, but it should suffice as long as we give others the impression. Today, we’ve gone a step further; playing dual roles is an enervating task, so we have chosen to kill the actor and justify the new, non-existent moral code. I chuckled thinking to myself – if Ray was this dim in his depiction of the 70s, what would he think of today’s world? Would the sigh of relief heaved by Somnath’s father become tears of joy?

Jana Aranya deals with the great growth catalysts of pre-globalization India with sublime tact. It takes us to see the world beneath, or rather inside, the buildings of “Goddess Fortune.” Sleazy posters and honest rackets galore but there’s no single actor to blame. If in all the films of Ray that I’ve watched, that’s the only quality that always stands out. You walk out with a burning desire to question yourself before the world. Though in the case of this film, you walk out with a desire to question how Ray’s prescience brought out the soon-to-be acme of the industrial world – a world where, regardless of consequences, we are quick to bristle like a middleman if needed. If the bar is too low, not to worry, we are ready to stoop like a dalaal too.