Halfway through Devi, there’s a moment fraught with spiritual undertows. Doyamoyee is preparing for her father-in-law’s rituals. He’s shown walking down the stairs – we can hear his stick click against the marbled floors for each step. An alms-seeker, sat at the footsteps of the mansion, singing with eyes fixated at the skies – “I’ll call out to you no longer, Mother” – referring to Goddess Kali. Ray cuts to Doyamoyee and we see her tug at her saree hearing her father-in-law’s arrival. The words tranquil, demure, and above all, content would be an unfairly inadequate tricolon to describe her at that moment. She’s divine being her compassionate, human self.

But Devi and Ray don’t wish to discuss divinity finding its residence in grace and compassion. There is no meaning or truth in compassion – it’s intransmissible as a mere human phenomenon. It needs a divine form to be comprehended. It needs to be apprehended and morphed into idolatry to serve men who seek truth, however incomplete it may be. Unfortunately, in India, our tendencies to pursue the latter have led to an inanity that has ultimately robbed both the worshippers and the worshipped. In Ray’s Devi, this inanity hardens in its final hour – Doya is robbed of her sanity, the Kalikinkars their son.

Devi, seen through Indian eyes, is a laconic shot not so much at religion itself, but its deviant superstitions. Ray, though rooted in empirical rationality, has nothing against spirituality and séances. Throughout the film, there isn’t a single sequence or shot that overtly maligns these practitioners – Kalikinkar included. The concern isn’t the cause, but the consequence. What is to happen to Doya herself? He follows the paces of rituals, premonitions, and dreams with such penetrative rigor that the absurdity of it all doesn’t belie what it is to its adherents. “I like to present problems and make the public conscious of the presence of certain social problems and let them think for themselves,” he says. He achieves his target, as he does in all his films, with a haunting panache in Devi. As Kalikinkar slumps against the pillars wondering why Maa took away his grandson, we feel a deep disgust for blindfolded belief than we do for Kalikinkar himself.

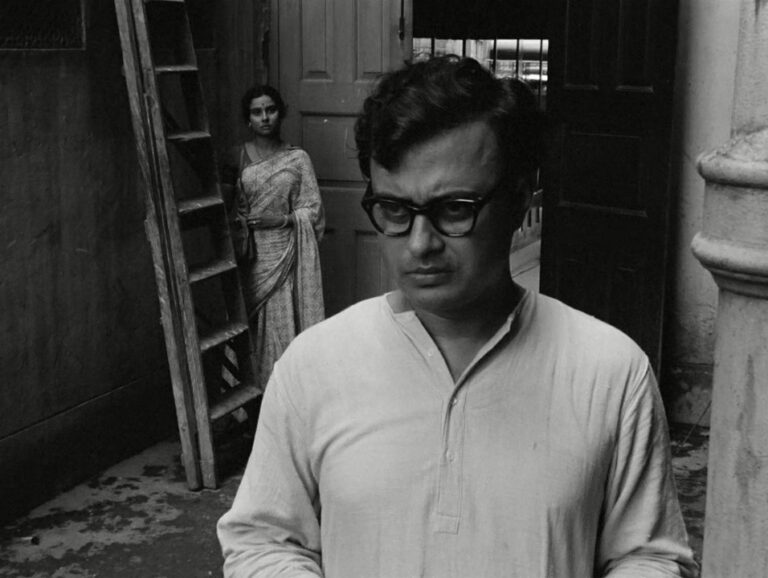

There are three discussions that fold together to complete Devi. The first of these is that of superstition and the dynamic between Kalikinkar and Doya. Devi takes place in a period when the Raj’s rule hadn’t fully steeped the Indian consciousness. Many of the customary practices are anachronistic and in some parts of today’s India, still extant. There is hardly a single instance in the film where Doya meets her father-in-law’s eyes to answer his questions or listen to his preoccupations. For better or worse, she has left herself in the hands of his judgement. When dreams of his are mistaken for divine visitations, all she does is scratch at the wall as he falls at her feet. Her verbal surrender completes a total surrender – she now has only an ordeal to go through, she can’t afford to think of its roots. Though the backdrop of Bengal was already fostering its own renaissance, certain regressive customs remained impregnable.

This ties into the second of the discussions that anchor the film – the dynamic between Kalikinkar and Umaprasad. Early in the film, Doya innocuously poses the question to Umaprasad – “Isn’t your father educated as well?” Umaprasad responds – “He is, but in the old ways.” Umaprasad is a Calcutta wantaway and feels that the port-city has no brambles inhibiting thought. He’s a slice out of Ray himself – rooted in Indian soil, reaching for the rest of the world. So then, there’s a firm schism between father and son that places two world-views at loggerheads. Uma views the world around him through the lens of another that is temporally ahead by half a century, and he’s disgusted by what he views. All the briskness in his pace is lost when he returns to see Doya made to sit firm as crowds swarm around her. He shouts with disbelief at his father, who is quick to return with a phrase from the Raghuvamsa to edify his son while indulging his own beliefs. Given Ray’s ideological disposition, Umaprasad is then placed as a mirror of the modern viewer. We see the film through his eyes, even when he isn’t present on the screen.

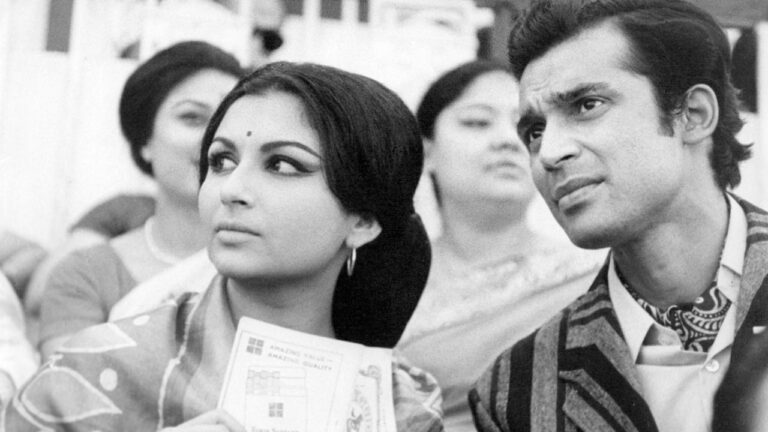

Nonetheless, the most important discussion of the film is that of the evolving marital relationship between Doya and Umaprasad. She’s an extremely young wife, an unsurprising fact for the times that the film chronicles. That fact reflects in everything she does – she’s docile and compassionate. She doesn’t have the luxury of age to ponder with pensive resignation about the circumstances that engulf her. To her, the reasoning of her husband and her father-in-law seem uniformly remote and detached. Ray’s objective was to display a malleable woman who is caught in between two opposing thoughts informed by two different worlds. When Uma escorts her to the boat he has arranged for their escape, she stops upon seeing the idol of Durga that has floated onto the banks. “What if I am the Goddess?” she asks meekly. Torn between these two torrents of ideas, she has lost her own agency of thought. Later in the film, Uma’s professor passes the verdict that his natural rights as a husband have been depredated. He cries against the foulness of how his wife has been entrapped by helplessness. To this, the professor ventures to ask – “Are you helpless? Why is it that you can’t protest something you wholly believe to be a lie?”. He stands naked without an answer. Umaprasad, too, stands between a romanticized set of ideals and the harsh reality of his situation. He’s unable to make his ideal world a reality and the current one a relic because he’s unsure of how much he’s attached to either. The ultimate truth of Devi is then a catatonic marriage – one where husband and wife are unsure of what to sacrifice to attain what they desire.

Unsurprisingly, like most of Ray’s works, the film only found acclaim away from home upon its release. Though it has since gained due reception across, the truth remains that Ray is still largely an unknown name to the Indian masses he strived to capture. Devi is masterful in how it induces a sense of claustrophobia within you; the dark walls, the narrow corridors, and the semi-lit bedchambers all mimic the nausea of intransigent superstition. With no respite, we are forced to watch the senile fantasy of Kalikinkar unfold as Umaprasad does when he stares down from the bedchamber window – motionless and exiled.