Ray sahib, as I’d like to call him fondly, is a man unlike any other. In any pursuit of art, one is forced to prod through the dark to hold something beautiful. Traipsing through bright nights, you see small flashes that the surrounding millions don’t. Your observation of the trickling life force of a nation that runs beneath its river of ordeals leads you closer to the warm sensations of true life. You try your best to wrap it and bring it back to share with those around you like a gleeful child returning from the sweet vendor. How well you preserve it while running back on the thorny road of memory is what defines you as an artist. In this aspect, I have seen no parallel to sahib.

I’ve seen many things growing up. I’ve read many things growing up. I remember my mother coming back from one of her weekly shopping rounds and she had a nicely coloured Amar Chitra Katha hidden at the back of the bag. I remember the hours I spent flitting through their pages of stories from the corners of India. I remember tugging my mother’s saree when I followed her around the countless temples she took me to. I remember the faces of the alms-seekers and my mother’s offering to them. In later years, I remember sitting on a coach to Bangalore, wrapped in the Tinkle edition between my hands. Lifting my head, I saw flower vendors and fruit-sellers heaving through the inescapable heat. Dropping my head again, I wondered how life must be in the dense Indian jungles where Shikari Shambu was in that Tinkle edition. In years much later, seeing the same faces of those alms-seekers, I’ve wondered what the price of my obliviousness hitherto must be. I’ve spent much time thinking about their paths in life. The basket of my experiences growing up in India has provoked countless tangents and emotions within me. In an hour and forty-five minutes, sahib makes me feel all of it again – and more.

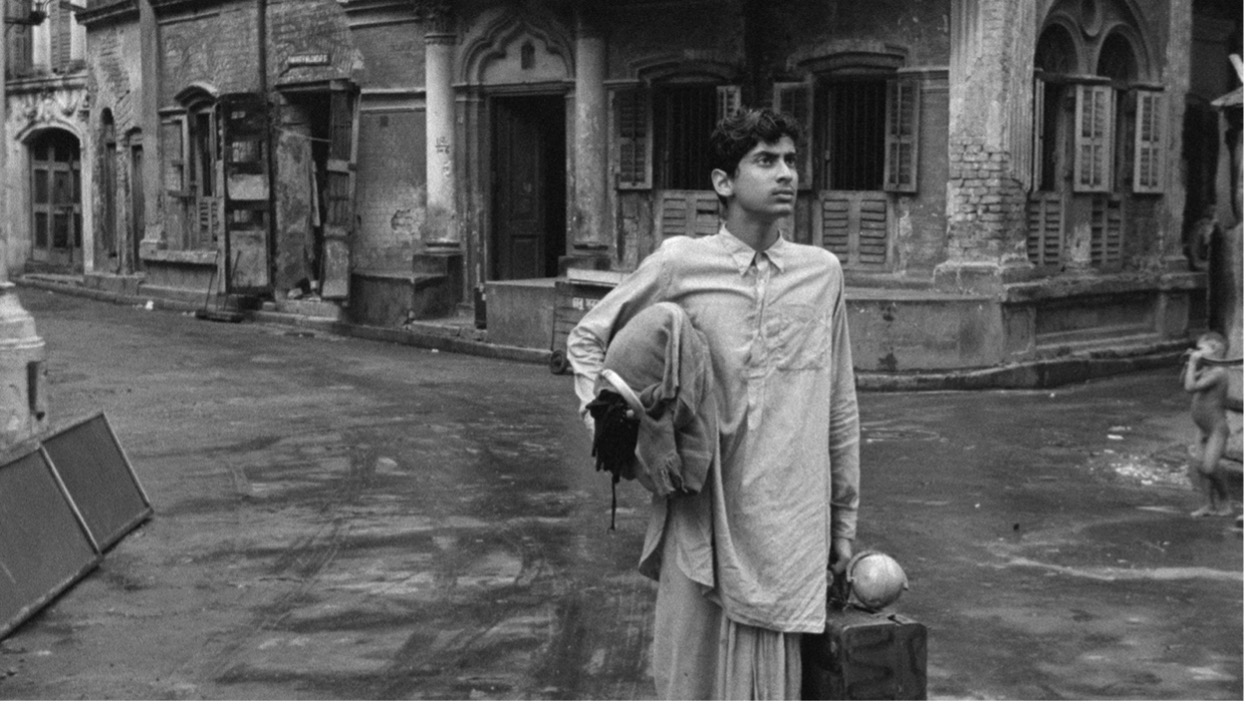

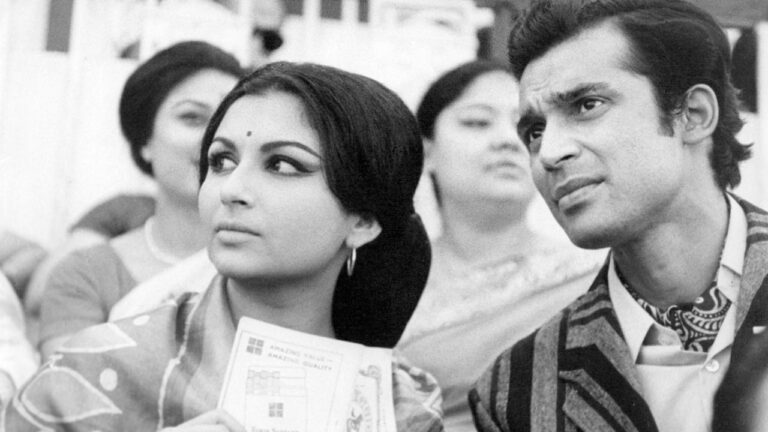

When I see Apu, globe and suitcase held by an unsure arm, I see myself. When I see his mother, I see my own. Across the trilogy, Ray has stitched his characters with a fabric that is so universal that every son in India can resonate with it to some degree. In Pather Panchali, with boys and their sisters. In Aparajito, with boys and their mothers. In Apur Sansar, with men and their wives. In each film, his observation of all the imperceptible moments floats them into an extremely intimate space. In Pather Panchali, Apu watches his sister be blissfully drenched by the Bengal rain. In Aparajito, the multitude of emotions his mother feels descending the stairs to see her son rejoice with the reward of odd jobs. In Apur Sansar, where Apu slyly pulls out his wife’s note and grins reading it, indifferent to his onlookers initially. In stitching these moments, he never attaches any tonal cues – he keeps them raw. We hear horns and hawkers, the rain, the roosters but no heightened music from Ray himself. Shankar’s sitar and flute are used sparingly. Without crutches to guide us to feel a certain way, he maintains the mirror-like quality of cinema. All three films constitute a legion where the “best” film is always the one you relate to most because there’s hardly anything to find dents otherwise. Cinema is already at its truest and purest form – like a lake that reflects your face without distortions.

As much as I love and relate to both Pather Panchali and Apur Sansar, Ray’s middle child has been the closest to my heart. Aparajito straddles the duality that I’ve faced and many do – the endless pursuit of the world while still being dug into the soil of your roots. In the later part of the film, the Headmaster of Mansapota dusts off a pile of books and places it in Apu’s hands and says – “Just because we live in a remote corner of a world, doesn’t mean our worldview should be narrow”. The images, the verses, and the depictions of foreign lands seem far too enticing for Apu. He dresses up as an African tribesman, reads out verses, and recounts foreign lands to his mother in a little montage. She smiles and walks away, bemused by these worldly affairs that seem beyond her concerns of raising her son. The verses drag Apu to Calcutta and he sees the steamers and houses that he’s only read about. They cloud his imagination and leave little space for the mother whose nest he has just left. Ray pulls this schism slowly but steadily until he rips it with an otherworldly scene at the end which drops the full heft of guilt and remorse on Apu.

That final scene has no parallel across all the films I’ve seen. Ray doesn’t criticize the act of pursuing the world – he realizes that it’s inevitable. Neither does he criticize Apu for being infatuated by all those images or verses. He simply observes these phenomena – as he does others in all his films – with a removed poignancy that is unbearably heavy when he drops it. He shows the struggles of a woman who wishes her son to be everything that he can be while suppressing that little desire within her to steal some more time caressing his hair as he sleeps on her lap. He shows how when you are wrapped up in your pursuit, your mother is walking through an empty house that doesn’t answer her grumbles nor probes her silence. It’s a guilt that devastatingly rains down on you when you realize that Apu isn’t someone else – he’s you.

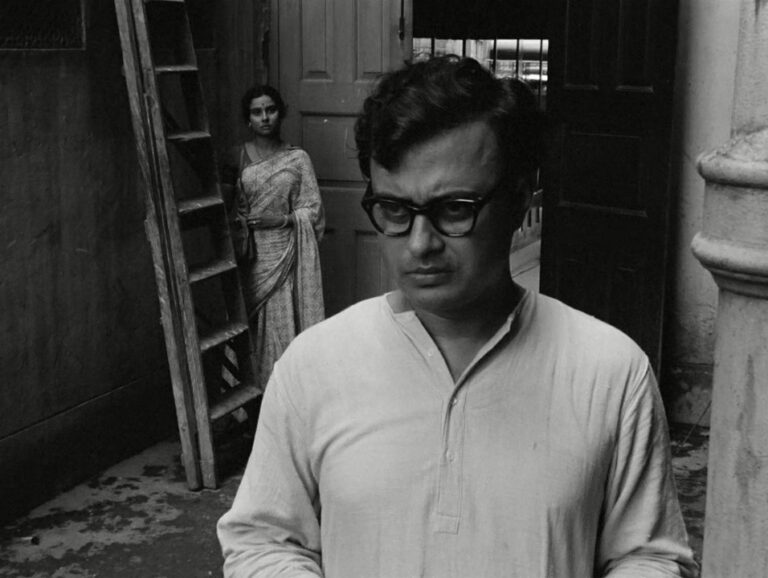

Ray’s cinema doesn’t excel in larger moments, rather in its more tranquil ones. He tugs at you gently, but you feel as if he’s ripping your façade away. There’s a sequence right before Apu departs for Calcutta again which captures all the emotion that is being diffused in the film. Sarbajaya prepares his meal and orders him to put his book down. She then gently asks him what he has seen in Calcutta. He swiftly responds – “Victoria Memorial, White House Lake, Stock Market, the Zoo, and Fort William”. She quickly retorts with – “What about the Kalighat temple?”. He lets out a yawn and says he was there a few days back. He goes to sleep while she recounts her troubled health. She asks with half-hearted hope if her son would keep her with him once he settles down in Calcutta. She asks him if he’d get her treated for her ailment. He’s already asleep and Ray gently inserts Shankar’s flute. She fails to wake him up on time for the train and he’s angry. He rushes to the station but he then walks back and tells his mother that he’d stay on for longer.

Within this entire sequence, the theme of the entire film is captured. Victoria Memorial and its environs are of more immediate interest than the Kalighat. The world is more alluring than the drabness of a life he has experienced much of already. Sleep steals him away from his mother’s recollection – not neglect. Ray doesn’t criticize Apu for his anger – he didn’t run off to Calcutta. Sarbajaya then holds back her concerns about her health to not worry her son any further. Apu continues his studies but comes back hearing about her deteriorating health. He walks through the house and turns around to see his uncle who looks at him solemnly. His image is haunting because it’s incredibly surreal and dream-like. Apu drops to the ground weeping and we cut to the night. His uncle tells him the only truth that we are aware of since birth – death is the only certainty in life. The next morning he declares to his uncle that he’ll perform his mother’s last rites at Kalighat. Life comes back full circle and Apu had to pay his price in flesh and memory to get it to start again.

I’m glad that Ray didn’t act on his other idea of inserting a love interest for Apu in Calcutta. It would have soured the film deeply with a needless detour to the real phenomenon and made that poor woman the bearer of all blame. Aparajito is timeless because the blame burns universally but claims no victims. The world is running ahead and you run to catch it. But turn back and see the cradle that you once rollicked in before Time and Death raise their sickle in unison. It’s pieces like this that inspire me to remain on the path to Cinema. To see and remember a frame that will fundamentally shake you at your core and never let you be the same again. Eternally grateful to sahib for giving me this mirror to course-correct and be the best son I can be before Death comes to collect its due.