What must it be like for one to be cosmically intertwined with a filmmaker? To have him populate the dots that have been rapped out by your current predicament? To label this phenomenon as eerie would be charmingly pedestrian. No, that isn’t quite it. Is it akin to the wound-up bird that limbers its wings as a response to the friction screwed clockwise into it? Perhaps. But, most befittingly, one could liken oneself to the parched-throat vagrant that hastens towards a stream. In his haste to soothe the gorge, he lowers his bearded jaw into the stream. The tongue laps the water upwards, disobeying the dictates of gravity. Having pleased his only master, he licks clean the droplets that now wet his beard. As the tongue rubs against his now-damp follicles, he realizes the painful state of his existence. An acute loss of agency fires the first bullet, and he bends forward once more. The reflective properties of water aren’t too kind to him either. He begins to wonder – have I become a victim to my circumstances? Or have I victimized my circumstances? One can never be too sure of having done either, but this self-portrait suffices to wrestle agency back into your own hands. Yes, this is how one must feel to be cosmically intertwined with a work of art.

My case? Rather peculiar. At 19, Aparajito lacerated me. Ray had shown me the dereliction of a world that careened past. The train of progress and the promises it houses often came at the dear cost of instability at the hearth. I was living in that world, nose ducked into lavish descriptions of Russia and the future to come in Europe. Thankfully, he intervened to remind me of the immediate world that then surrounded me. Now, facing the uphill task of finding a job for the summer, I’ve exhausted myself in endless conversations that judge my suitability. I’d sit there and present myself only to be dismembered like a frog that croaks under the blade of a 9th-grade anatomy fiend. Days and nights roll into one, and sometimes, the thoughts of weeks past jut into your current stream of consciousness. Doubt, an old friend, drops by to render friendly visitations. So then, imagine my amusement when I sit down to watch Pratidwandi. Here, Ray has gone a step further in reassuring our cosmic relationship, for his aimless protagonist and I share the same name.

“Siddhartha,” begins Adinath, “there are two kinds of people in this world.” “The thinkers, and the doers,” he continues “and I belong to the second category.” Having calmly placed his friend in the first, he indicts him for inaction. Rubbing shoulders, they find themselves in a Chinese restaurant. When asked about his drinking, he says, “What’s there to learn? It’s hereditary.” Perhaps, the vice of thinking is a hereditary burden too. Or, if one is superstitious, it can even be termed an eponymous burden. Only that my namesake sat under a fig tree whereas his borrowers in name sit under the suffocating, closet-sized rooms of our dear metropolises. But true to his protagonist’s name, the film marks a scathing change in Ray – there are no lyrical soft-landings to cushion the blow of his stern gaze of 70’s Calcutta. It’s long and heavy-handed in its depictions, and there are no brief departures, as when Apu and Durga run through rice fields in Pather Panchali to catch a glimpse of a train tearing through their pristine cove.

In broad strokes, Pratidwandi is an exploration of identity. Not just that of the individual, but the collective as well. Early in the film, Siddhartha attends an interview. As he exchanges in high-strung English with his interviewers, he’s posed a sharp question – “Who was the prime minister of England at the time of independence?” He rejoinders with a carefully weighted response, “Whose independence, sir?” It’s a tongue-in-cheek remark, one very befitting the sardonic tastes of Ray. Here we are, three spruced men, sitting in ties and polished boots, speaking the colonizer’s tongue with such pointedness, only to ask the self-defeating question of independence. It reminds me of Captain Bhau, who recapitulated it best. “We fought for two things – independence and freedom – we achieved Independence,” he resignedly says. Independence was merely the external act, the unshackling of chains, the pressed exchange of hands to thank for the transfer of wealth, repaid by a nicely repackaged idea of civilized liberation. Freedom, however, is the internal act – when we stop associating advancement with the foreign tongue. Ironic, isn’t it? To type this out in English as I say it? I shan’t probe this too much, for I am also grateful for it in the sense that it links me with the other tongues of my land without the invidious cost of linguistic primacy for one.

Ray chose his moment to foray into politics. Calcutta was in an internecinal rut – the students were fighting against the established order. Matinee shows had more flares in the seats than on the screen, and the unemployed masses were jammed against each other on footboards like low-hanging fruits. If this was the hour of the revolutionary, then it was also the hour for the portraitist of the revolutionary. But for Ray, to be political was never the issue. “I always felt that,” he tells Sight and Sound, “that politics in India is a very impermanent thing.” He didn’t wish to engage in the ever-transient. But the fracas of Calcutta was too loud to ignore, so he decided to chart its path. Not through the revolutionary, for there’s nothing to explore there – it’s a straight-lined plunge. He chooses a man affected by it, but being aware of its personal consequences wishes to remain outside of it. Courage-deficient would be a suitable diagnosis, but gashes inflicted at every turn will remedy it. Overall, the perfect choice – one that symbolizes the lathering tensions beneath the straight arrows of revolution and order.

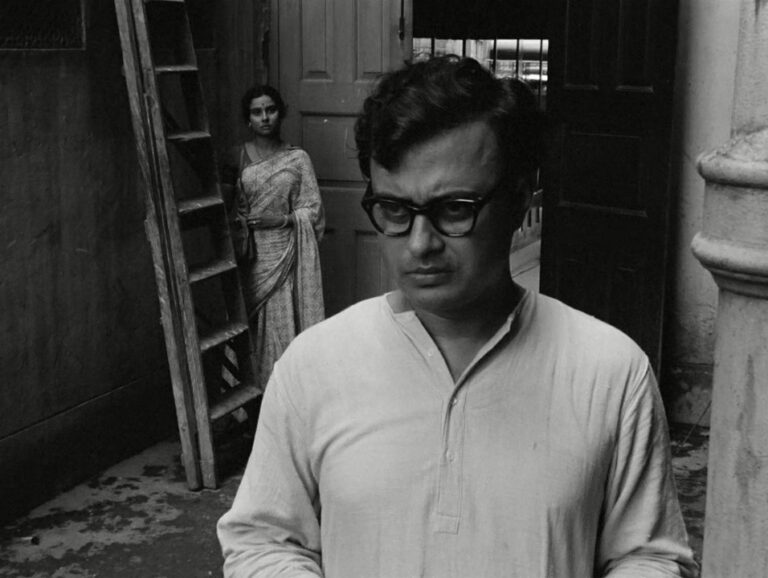

Following such a topsy-turvy path meant that Ray needed to fashion stylistic changes. For a brief moment, I was quite shocked by the negatives that opened the film. It seemed so far away from the orchestrated lulls of his early films, almost amounting to a momentous schism. With each step after that, as when he tracks Siddhartha with the looseness of a Steadicam, the old Ray was falling apart, and the new Ray was being fitted on fast enough to keep the film moving with a slink. There are other markers of this new order too – the reluctance to hold onto an image is perhaps most notable. When Siddhartha, siphoned dry by Calcutta’s heat, sits in the shade of a portico, he’s vacillating between many things – the reminiscent river in front of him, the less fortunate washing their clothes, and finally, the hippie circus that gatecrashes these observations. For much of the early sequences, Ray doesn’t let Siddhartha settle down, and through him, the viewer as well. This strain of disconcertment is constantly seamed through the surface narrative. Peculiar associations are made by his unsettled mind – the anatomy classes of years past pepper commentary to punctuate the cog-in-the-wheel behavior of many. It’s as if his mind is making a deeper observation of Calcutta’s throbbing society; everyone is running towards something, increasingly aware of the destination, less aware of themselves. The logical prognosis? A room full of skeletons stitched together with skin only for appearances. Stripped of all agency, subjugated to a slave-driver at every turn, silenced until quiet obedience is self-affirming.

Ray is extremely bleak in bringing out Siddhartha’s unidimensional worldview – and the two most non-Ray devices he uses to accentuate this are image negatives and dream sequences. With the negatives, the focus was to alienate the audience – as a way to say that “this isn’t an event to read into.” The two instances, the death of Siddhartha’s father and the visit to a prostitute, had negatives for different but similar purposes. One was to make the personal event of death impersonal and less consequential, and the other to appease an otherwise conservative audience. From the perspective of the narrative, however, both are lows for Siddhartha – he is visibly consternated by the death of his father and the death of his morals. Both moments are merely a flicker, an indication that one’s dwellings at rock-bottom are of insignificance until one is made overwhelmingly aware of them. On the other hand, the dream sequences are a passage of heightened realization. Of what? The most likely answer is his stagnant impotency. A sister astray, a brother at peril, the interviewer’s cabal – all are entities that thwart his feckless efforts. Faces morph and he is no longer sure of what he attributes to which. Only languid daybreak can rescue him, and when it does, the next night’s taunts rent his thoughts. Ray has abandoned his Indian bearings and screwed on the penetrative lenses of Bresson and Truffaut in these passages, and perhaps, even a bit of Bergman in his dream sequences.

Nonetheless, what is unique to him is his wordplay. Certainly, a benefit that he borrows from Ray the novelist. “Can you lend me this?” Siddhartha asks Adinath about the Playboy magazine that he’s flipping through. “Do you know its resale value? Ten rupees per copy,” Adinath snaps back. When Siddhartha broaches the question of trust, Adinath responds, “Look, I don’t trust the unemployed.” Moments later, Shiben sticks a cigarette in his mouth and proposes going out for a movie. “Again?” Siddhartha demands, to which he responds with a smirk, “Swedish movie, no cutting.” In this insouciant talk, Ray establishes the air of the film; young, agitated men are aimless and as a result, perverse too. Morals? Whatever remains of that sags like a week-old drumstick. They wander from the film to a nightclub, and from there, onto the poorly lit streets. The pace of their feet mirrors the pace of their mind, and thoughts enter and exit at jagged angles. “What’s wrong with your personality,” probes Shiben, “it has the stamp of intelligence.” Siddhartha, exasperated by this appraisal of what isn’t lacking, punches back, “Who wants intelligence? You understand everything and pretend to be a fool.” He understands, and so does Ray. What place do sharp wits have in a world that is threatened by it? Sit, drink your gruel, bob your head, and get the task done. You’d be rewarded with kind adjectives and that should be incentive enough.

There are other, smaller allusions too. Siddhartha drops his watch – an inauspicious sign, as we would say. He takes it to a watchmaker, who quotes a price too heavy for his empty wallet. Time does come to a standstill, and there is no indication of whether the events come to take place over days or weeks. Unemployment is then a painful state, for you’re walking when everyone else runs. They have an urgency that you no longer have – you are free to observe and adjudicate without the burden of a nagging wristwatch. Yearning for interactions, you are chafed by their first embrace. Like a silhouette draped against a wall corner, the stampedes of the world rub against you, and smothered by it, you fling imprecations. Walking back after assassinating Topu’s boss in the fields of imagination, he joins a crowd to thrash the driver of a hit-and-run. Why? Is he angry at his own impotence elsewhere? Such may be the case, but it’s a sign of a timeless existence – he dreams during the day, lives through the night, and in fleeting moments, he forgets his temporal orientation and performs the actions of one state during another.

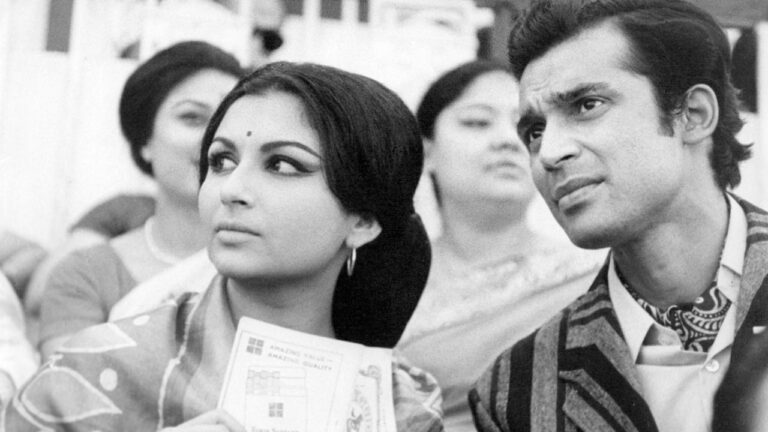

There’s a lark. It keeps calling to him, and he shuffles through night markets and their illicit cages for its call. It finally appears, in the dead of the night, from the dark recesses of an upper-middle-class Bengali house. The fuse has tripped, she needs assistance – and Siddhartha seemed harmless enough to help. But the call was more than just a fix for a tripped fuse. Keya, short as her appearance is, becomes consequential in the two or three encounters she has with her rigid companion. She’s soft and unassuming; the turbulence of the outside world has left little to no impression on her. Contrary to the strifes outside, she’s mired in a familial predicament of her own. Her eyes traipse and settle down on him as they walk above a Calcutta that is now of less moment. Acquiring clenched jaws and frigid tendons, he looks away from her. Ray brings two exiles, each desperately in need of the warmth promised by the other. Siddhartha, at some level, is aware of this. Yet, the monstrosity of the prevailing order finally draws his blood. He’s shipped off to Balurghat – and he’s met with the lark’s call again. Again, Ray doesn’t romanticize the idyllic, both its physical manifestation through Balurghat and its quasi-marital manifestation through Keya. Neither promises an easy segue, but what can one know only from prospecting?

Seeing Ray over the years, I’ve come to realize how towering his presence as a filmmaker is. Not many – and I don’t say this lightly – have the ability to shift between vastly different tonalities, landscapes, and characters. He toggles between them with such ease that one soon realizes that, as a filmmaker, you’re one true asset is your way of seeing. You are in a perpetual metamorphosis with rational scissors as your vertebrae. You sever the potential flab – the melodrama in Aparajito, the prosaic in Charulata, and the seditious in Pratidwandi – and jump straight into the pith. How you do so, and what you determine to be flab, are left to your devices. But there’s an essence, the non-duplicity of an image, that needs exposition – and here is where you learn to observe. Do it long enough, and the act of observation devolves to become your de facto worldview. This de facto worldview is what you’d need to shed as you metamorphize, suitable to the milieus of Mansapota, Benares, or Calcutta. An exhausting existence, isn’t it? Ray did it nonetheless, and he left, to paraphrase Kurosawa, like the sun and the moon themselves. I’d love him forever more for this, and until I come back to chronicle him for the next time: Yours Truly, Siddharth(a).