This week of cinema has been devoted solely to the surreal and the beyond – between Scorsese’s “It is accomplished” and Bergman’s “It is finished”, I’ve managed to plumbed faith beyond semantic barriers. In many ways, Scorsese’s work was a necessary predecessor because you appreciate a world that depicts the divine’s abject silence when it quickly succeeds a world that emphasizes nothing but the word of God. There are a hefty 1000 odd years between the Black Death and the death of Jesus. Separated both temporally and geographically, the interpretation of God has had many manifestations in-between. Unlike Maylov’s classical quip – “The darker the night, the brighter the stars, the deeper the grief, the closer is God” – Bergman gives no godly reprieve in his construction of a brutally grim and cynical world in The Seventh Seal. Its participants continually knock on God’s door only to receive his severe silence.

Before delving into the heart of the subject, there’s a very interesting observation that I’d like to make from a bird-eye view of two directors who have been symbiotic throughout their existence on the grandest of stages for over three decades. Tarkovsky, the Russian counterpart to Bergman, also established prominence in the ’50s with Ivan’s Childhood. Structurally, Seventh Seal and Ivan’s Childhood are arguably amongst the most conventional sojourns in their oeuvres. They both follow an arc wherein the central character goes through a spate of tribulations before meeting their fate at the final destination. Through the middle phases of their careers, they both banked heavily on the subversive and unorthodox – Bergman with Persona and Tarkovsky with Mirror. Though Tarkovsky didn’t have the benefit of a full life, unfortunately, Bergman did move back into the more conventional with his television productions, most notably Fanny and Alexander. In these later stages, they’ve teased supernatural realities within the paradigm, but they haven’t teased changing the paradigm itself. Across a director’s own body of work, such eclecticism is in and of itself a mark of ability to prescribe different treatments to different subjects. Every single time you try and break down the pieces of your own approach to cinema, you’re able to deliberate which piece of a structure suits a subject best.

Now, into the subject. The Seventh Seal isn’t a question of if Death would spare you, it’s more a question of when. Bergman took many historical liberties in sewing together this narrative to seem impenetrably bleak – he borrowed two hundred years in advance when he established witch persecution as a practice in Sweden and deferred the crusades by a hundred to coincide with the onset of the plague. The film opens with extensive establishing shots of two men on the beach – a knight and his squire. An ominous chess board balances itself precariously on a rock. Death arrives and the Knight halts the swift blow by challenging our omnipresent creditor to a game of chess; If the Knight wins, he gets to evade death for a day longer until he finds meaning for a life he has come to regret.

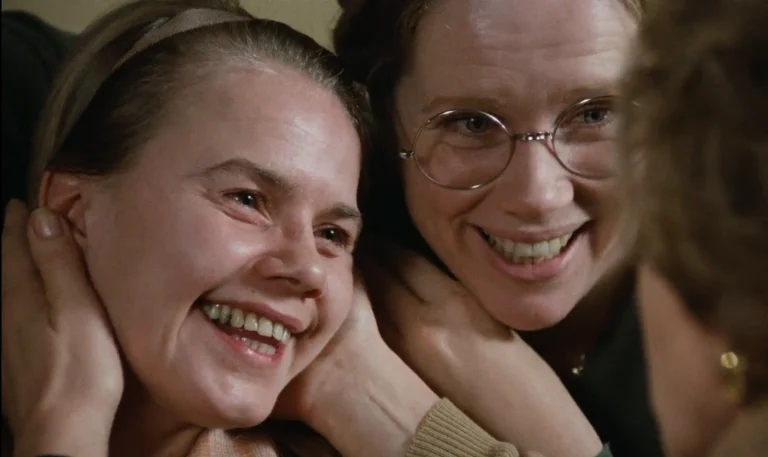

Looming bleakness, however, doesn’t deter cackles and grotesque displays. Men drink until their nerves fail them, women abandon fidelity for promiscuity, spit and cheeky laughter are the only dividends for performing arts. These slivers only serve to underline the fact that man is far more skillful in plotting his own downfall as opposed to nature. Our divination of the horrors we are yet to experience proves counterintuitive – instead of lulling ourselves into acceptance, we frenzy and accelerate its arrival. In a major sequence halfway through the film, hordes of men and women walk through the town’s centre, upstaging the ongoing street performers. They flagellate themselves and decry the decay of sin and lay down the path of punishment we must follow to retribution. The darkness that creeps around the corner has prompted man through the centuries to more despondent interpretations of divine silence – we turn inwards to purge ourselves. But in this purge, we often overlook the spots of brightness. Bergman, however, doesn’t. The few instances in his film where the frame is filled with more light than darkness are when Jof and Mia, two travelling performers, play with their son Mikael. In a caravan that pootles along (yes, being in Britain has started to affect my verb choice), their jest and laughter dim the rapid degeneracy that surrounds them.

Within all this, Block earns his reprieve and continues to hold a stick out for a word whispered from the divine. His dynamic with death is interesting. The trope of bargaining or fooling death to remain amidst mortals has since been launched into public consciousness through the Harry Potter series. Bergman himself stumbled upon it in a painting he found at the Täby Church. From the outset, you are made to realize that there’s only delay and no denial – denying death is never a possibility through the bodily vessels we inhabit. Block too doesn’t wish to deny death, he only wishes to find an antidote to his current disillusion with a God that raised his sword but refuses to answer his pleas. He even implores a witch, a woman of Satan, to summon her master so that he can question him if he has seen his counterpart. Sydow’s chiselled grimace wrenchingly displays a modicum of terror, a modicum of despair, and a modicum of tenderness when he sees her writhe with pain. He eases the woman into death’s cradle before turning to Death himself who chides him for his persistence with these questions. However, you see that he mellows with compassion when he sees Mikael and Mia. Sipping the fresh milk and biting the wild strawberries they offer him, he states that if there’s a memory he would carry into the eternal, it would be this one. When Death revisits, he disturbs the chessboard to help the buskers and their son evade Death for a little longer, and we see that glint of compassion easing his eyes again. As he sees their caravan trundle away, we finally realize that he equated the only perceivable phenomena of compassion to godliness that warm afternoon. In doing so, he relinquished his last reprieve.

Films in the vein of existentialism aren’t new to me. The only film that I’ve viewed in recent times that impressed itself upon me with similar force was Mizoguchi’s Sansho The Bailiff. Both Seventh Seal and Sansho emphasize the grandest of all platitudes that take a lifetime of suffering to sense – the relegation of the self and the exaltation of selflessness. There, in the only reprieve he earns after an unforgiving lifetime, Zuishio outlaws the horrendous slavery in private estates before he resigns. Here, Block distracts Death to allow Jof and his family to escape. That moral compunction bit Zuishio harder as he saw his sister walk into the lake to avoid the monstrosities that await. With Block, it gently blew across him as he saw the life he could have created had he stayed back instead of the years he spent with the Crusade.

But these moments show themselves only when the bleakness is painted as thickly as possible. Else, when the burden lifts itself, the realization can risk falling flat. Whenever you try to sear bleakness, your scope necessitates you to be as wide as possible. Almost every director who resides in a league above the rest – Tarkovsky, Kurosawa, Mizoguchi – does this and so does Bergman. If you take Seven Samurai for instance, when the village gathers around the Samurais, we see that when the Katana is thrust into the mound followed by Kikuchiyo sitting down, despondency ripples through the rest. In Andrei Rublev, when the bell oscillates backward and forward before striking resonantly across the landscape, there’s wrenching despair on everyone’s face, including Andrei. In Sansho, Mizoguchi shows the now freed slaves dancing to their former master’s seat, destroying everything in their path. Earlier in the film, we would have seen them glued together, cowering and writhing en masse with every branding or whip. Scale, therefore, becomes extremely important to impress this; carefully alternating between master shots and wide shots that accompany blocking and composition are more pivotal when showcasing how extraneous emotions ripple across an entire population. Here, Bergman does this as well – the composition of the shot when people move across the landscape flagellating themselves, the smoke emanating from the pots, and people bowing to acknowledge the sin they have been accused of. As a director, he often doesn’t get the same visual credit his peers elsewhere do because his films are moved much more by the force of dialogue and structure. I felt it necessary to point out that there are moments of carefully wrought-out movement that accentuate his philosophical exploration.

Filth, or the abject absence of either remorse or morality, is another interesting off-shoot when one speaks of the plague. Bergman’s treatment of the subject is similar to Camus’s treatment of how filth sets in during The Plague. In The Plague, Father Paneloux laments the profligacy of Oran’s populace and deems their behavior to be a catalyst of God’s punishment – the plague. Once their impending peril accelerates, they become detached from religion and its moral code. When evangelists shout, Rieux notes “they all make haste towards some trivial objective that seems of more immediate interest than God”. Bergman too showcases this – rape and thievery are rife, Jof is belabored around the head as the townsfolk watch on with mugs of beer banging the tables. Real despair is when men revert to basal pleasures – they wish to exploit every bandwidth of pleasure on offer before they surrender themselves to Death.

As Death dances away with his captives, Bergman appeals to us to find our only solace in compassion for the only device we have in our hands to delay death – the gift to beget life and the capacity to nurture it.