Sunrise may quite possibly be the only silent film I’ve ever watched so far with the maturity of a moderately experienced viewer. Even perchance, I have no memory of watching anything else over the last few years – even on television – from the silent era. Hence, I shall not wear a mask of pretense to opine about what may or may not have been the intended nuances of German Expressionism to the extent that my restraint allows. Sunrise itself, however, as its creator proclaims, isn’t associated with the tribulations of any land. Murnau fondly calls it the song of no place and every place; it exists where men and women do.

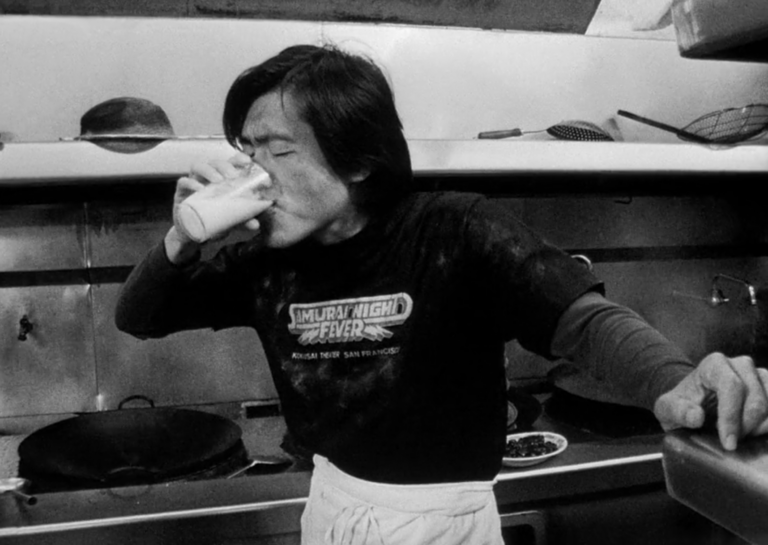

If Cinema were an entity of flesh and blood, it would have been a roguish teenager when Murnau arrived in America. It borrowed from everywhere and presumed it owed nothing to anyone. It seldom speaks but speaks platitudes with a revitalized panache. Flamboyant but perpetually on tenterhooks, it’s a dazzling age where the medium existed more to excite than evoke. Murnau displays flashes of this as well – the garish and salacious lights of a Metropolis which pour from the pitcher of electric life into a newborn marriage. A man packed out of Germany and chased into the arms of America, Murnau was hot property; once the roiled bitterness of the Great War settled, Nosferatu was appreciated after it was imported to foreign shores. All of this served to give him what penny-pinching studios wouldn’t dare to give to most makers today – unfettered access to all his demands. What this liberty gave birth to was a film that, in many ways, truly defines cinema’s transcendental quality that can stand upright without phrases. Since much has been spoken about the circumstances of the film, I’d like to focus on what I saw that made me arrive at such a conclusion.

What makes most films from the German Expressionist era – most notably The Man who Laughs by Paul Leni – stand out is their delicacy in lighting. The early crop of filmmakers didn’t have many devices at their disposal when shooting as compared to the crop of this century. Yet they manage to create a sense of dread by toying only with the modalities of light more than what we’ve managed to in this generation. Fear and dread are precisely orchestrated to the gradient of light; in Sunrise, Murnau has achieved this in the same way Meyer fashions the narrative – without obliqueness. The first act of the film is set completely in a low luminosity that is reflective of both the Man’s actions and his state of mind. The image of him lying down in bed as he fixes a gaze on his wife is impeccably constructed. The light falls exactly where fear displays itself the most – the unflinching eyes, the twitching nerves, and the perspiring forehead. Darkening over the rest, Murnau shows us precisely what needs to be seen.

This absence of obliqueness permeates into the way his scenes are edited as well. It’s a didactic tale, but you never let what you wish to convey stray into the open. You’re always walking on a tightrope; you don’t want to alienate your viewers with a shroud of subtlety. When the morning arrives, and the Wife tends to her chores, you see the Man watch her with sunken eyes from his bed. There’s a guilt that’s charring within him, but Murnau doesn’t fan it. It’s immediately followed by a series of superimpositions – the woman from the city fondles him invitingly. A neat editing trick that counterbalances the emotion before it can morph into an excessively suggestive display of wrongdoing. Her hands are placed over him with such perfection that I can’t stop admiring Murnau’s ingenuity and contemplating what could have been if he were born in a later era. Then again, a true artist’s gumption is born through limitations, and Murnau has done everything to justify the reputation that precedes him.

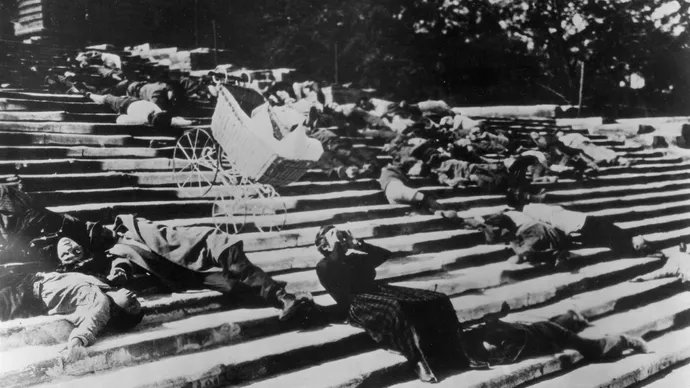

The entire film hinges on one particular sequence. It’s the intended act of drowning the Wife by the Man. It’s this particular part that segues the film into the redemption arc and Murnau’s sheer mastery of the craft dapples through in the pace, the swift and painless shift of the mood, and the jagged angles. It achieves everything that an Expressionist strives to achieve – the inner turmoil of the couple changing to bliss as the landscape changes from the countryside’s dourness to the city’s extravagance. The internal and external states are knotted together, and the film moves into the phase of relief with no snags. We see them sitting on the boat, and the Man starts rowing after the initial mishap. She’s clasped her arms in caution, and she watches him with her reservations. Even in broad daylight, the contrast under his eyes still shows. When he moves across like a log to perform the act, Murnau keeps his face in a close-up (which occurs very selectively throughout the film), and once the music crescendoes, it gathers a pace that doesn’t stop until the landscape has changed completely. This needed to be swift, but the complexity of the emotions may have prompted others to draw out this change. Yet Murnau slides in everything his school of expression demands from him and manages to pad the film evenly with the two valleys of emotion on either side – temptation and persistence in married life.

For some, the problem with Sunrise may arise from its one-dimensional characterization. The Wife is a symbol of goodness and compassion, and the Woman from the City is everything that is not. The Man, then, is the confounded chap who needs enlightenment of the virtues and vows of marriage. It’s a tale to be told from the pulpit during a languid Sunday mass, but in Murnau’s hands, it’s not religious lecturing; it’s the artless state of devotion, if not to God, but between two willing participants in life’s extension. We see them enter the Church, but the real tutor is memory, not the sermons nor the vows. There are layers to the characters, but perhaps, it isn’t necessary for what this film wants to achieve that they need be anything more. Early cinema emphasized conflict fomented through the exterior more than the interior. Still a spectacle, it was perhaps only seen as an avenue of excitement. We see the Man and his Wife dance in the towering sets of the Metropolis, and it must have been a treat to watch for its viewers as much as Lang’s Metropolis was. The lens that sets the search for layered forces of internal conflict is better aimed at the Cinema of Bresson and Bergman who profited from rolling back the long years of marriage between the screen and literature.

Nonetheless, speaking of Sunrise on its own merits, monochromatic characters aren’t necessarily a bad thing. The film’s real exploration is the aspect of cinema that acts to separate itself from literature, to plumb a type of characterization that is penetrative and not expansive. The characters are less dominant as opposed to their surroundings and even the Woman of the City herself is more a caricature-ish externality. It’s the couple that forms the core of the film, bouncing off all external developments. They are so malleable that one needs no dialogue to feel their changing states; their verbal agency is castrated, and we only hear about them as one hears about a myth or folktale. It wasn’t until I finished Sunrise did I realize that no dialogue, little dialogue, and verbiage all add three very different layers to a film. If this film of Murnau is on one end of the spectrum, then Berlanga’s The Executioner is on the other. There the verbosity pedals the film from act to act, here the impressions of the environment do the same.

Sunrise was a very brief detour. I didn’t wish to miss the rare opportunity of catching this film on-screen and I have a silent gladness that I did. But I’ve also realized that I feel acutely ill-equipped to reflect on the film without knowing the era itself. I’d return to the early years of German Expressionism when I do a round of the films there, but for now, I’d return to the 50s and 60s where the medium spoke little but said so much.