“It is easy to be King of Kampala,” tells Okelo, saddled with resigned frustration, fanned by the flames beside him. “Why don’t you try to be King of London? Or King of Bombay?” he provokes Jay. There’s an unvoiced tension between the men, one that seems simultaneously prolonged yet sudden. Both Okelo and Jay have been placed in front of the racial lens that fraternal relations try to avoid – what Nair herself calls “the hierarchy of colour”. Brought out into the open and congealed by this dialectic, she tables the crux of her discussion. A grand venture to chart the mishaps caused by the mere gradation of skin – from Kampala to London to Southern Mississippi. Often, when a filmmaker humps the weight of such a dominating discourse across lands that are engaged in varying stages of its specifics, he or she fails to temper his or her temptations to universalize. So, what has Mississippi Masala achieved with these ambitions?

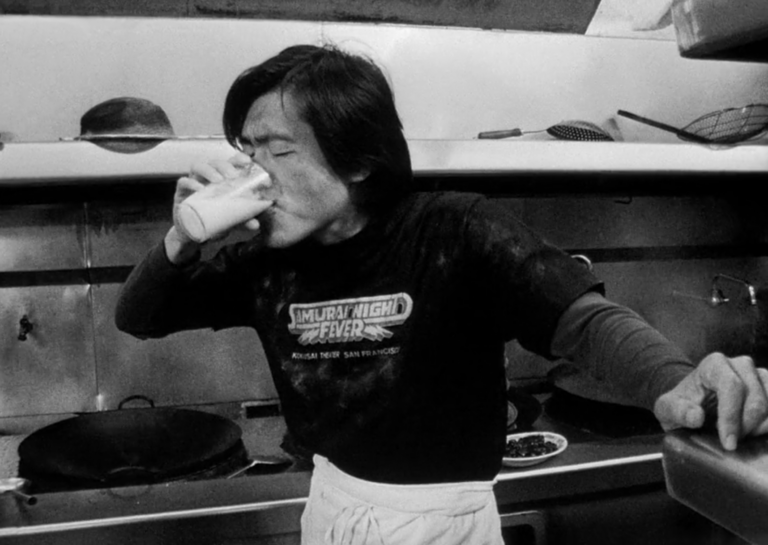

For starters, authenticity. With such a broad-based canvas, Nair’s understanding of the circles that cross each other veers her film away from the usual lip-service tirade on race relations. Be it the expansiveness she breathes into Uganda’s ambitions, which through conscious selection break onto Lake Victoria’s length and breadth at dawn after Jay’s clean break with Okelo. Africa is born anew, but severances have had to be made. To this sentiment, indiscriminately, Nair does justice by being faithfully observant. Even when she flies her film into Mississippi, she continues to hit the right note. Her willingness to engage Denzel Washington on matters related to the African-American community unties all the characteristic stiffness one has when the portrayal of a diaspora mindlessly confirms one’s already threadbare conception of them. In a few other films with a diaspora focus – Chan is Missing being the only notable one coming to mind – the authenticity of life-like nuances forms an integral ancillary pillar. In Mississippi Masala’s case, the strength of the ancillary pillars accounts for much of the director’s accomplishments given how much it contributes to keeping the film aloft without crumbling under the weight of its principal thesis.

Truthfully though, there’s an even finer silver lining that keeps Nair’s film charged even in the rare absence of authenticity – charm, the captivating menthol that diffuses an unspoken yearning for postcard pictures, breeze, and beach shorts. Even in a film that speaks about the side currents of American and Ugandan life, Nair tugs at the broader cross-community spillovers of modernity and tradition that bring them together. In Uganda, the transversal vista of flora and fauna presents itself to Jay -as do the beaches of Biloxi to Mina – something that they’ve never truly possessed but have always secretly laid claim to. A whimsical desire for spotless beauty, one that all of us entertain, and upon attaining, struggle to keep alive. Pairing with Nair’s authenticity, this wistfulness of Jay and Mina interpolate her main thesis on race relations, despite their short-lived play to tap into the viewer’s nostalgia.

But to what effect does this combination of themes amount, except for the latter’s transient relatability? Separation and nostalgia – at least at this scale – for both what was lost and what is being lost form a large enough fracture in Nair’s primary thesis on race hierarchies. Sure, you could say that they aren’t mutually exclusive, and race’s disturbances have set these aches in motion. But if there is a unidirectional relationship to be explored between the latter and the former, it can only tie itself to one region for specifics are never truly the same across geographies. It’s for this reason that Jay’s blotted dreams suffer owing to Mina’s breakaway rush across the Southern landscape and to some degree, even the opposite takes effect. The ambitions of a filmmaker that I’d spoken of earlier often work to the detriment of him or herself and in this case, they’ve snared what Mississippi Masala could be in more ways than one.

Speaking of fundamental foibles, Jay’s trappings in the past – and by extension Kinnu’s too – form some. When I’d touched upon the merits of Nair’s authenticity, I skipped out on her portrayal of the Indian-American community with good reason. Diaspora spotlight isn’t always easy, especially when one is seeing an extension of one’s own community through the brambles of their adopted culture. However, to her fortunes, the portrayal of the Indian diaspora in Uganda seems far less trivial given its diluted focus than what resembles a near caricature-like portrayal of Indian-Americans. Southern Motels, from what I know, may or may not be sober places of business. But there’s a very distinct outsider gaze – one that pins itself on the weaknesses of the diaspora – that hasn’t been very different from the image painted of them for years. True, there are moments of sincerity – as when the community sits down for a morning prayer – but they still play within a very safe circle of clichés. Their close-mindedness, which is what I believe Nair tries to poke at from discreet angles, isn’t so much a problem by itself. It does become one when it bridges Jay and Kinnu’s unique yet arrested character developments. Their decisions and opinions on Mina’s behaviour jut unnaturally from their otherwise differentiated personas. With her efforts pinned onto ancillary pillars, Nair has left the few principal ones to implode. The consequences? Engagement with her main thesis on race relations stands on weak grounds due to those most affected by it.

These weak grounds, however, aren’t solely due to a discontinued evolution. Frankly, her distinct outsider gaze places these characters on them from the start. Funnily, given how recent my viewing of Chan is Missing, where another homeland director directs a diaspora, it’s almost apt that I place it side-by-side with Nair’s Mississippi Masala to contrast approaches. Wang, much like Nair, moved to the states as a Hong-Kong native years before his first day of shoot on the sets of Chan is Missing. He, unlike Nair, didn’t make the Chinese-American struggle the pulsating heart of his story. Surrounded by the West Coast catalyst for the 70s Asian-American movements, his mind was preoccupied more with the medium itself. Nair, right off the back of her hard-won scholarship, was walking around the lawns of Harvard, and Mississippi Masala descends directly from the stifled mobility, as she perceived it, between white and black communities around her. One begins with fealty to the idea and the other with fealty to observation. Neither is wrong, but I mark it at the outset because, in Nair’s case, it works counter to what her film encompasses.

Though her initial perception, valid in the context of the region she saw it in, is misguidedly shoehorned onto the terrain of Africa. Race, or the hierarchy of colour, has existed in varying degrees throughout history but has never been more explicit than when being a Western idea. In the South, racial tensions have been rife, and Nair’s not-so-discreet exposé never hangs unnaturally here. But when extended to Uganda, the forced extension cuts outward visibly. Amin’s decision to push the installed Indian population out of the country is certainly of Western origin. Imperial remains continue to have removed effects – a very weak, subconscious fifth column one could argue – in the wake of Independence. But they serve poorly to explain, as larger forces at least, the dialectic between Jay and Okelo at the start of the film and in passages looped in between. “Africa is for Africans. Black Africans,” Jay restates Okelo’s words to Mina. Okelo may or may not have believed in this imposed construct, but the abruptness with which his categorical statement is made leaves us questioning the path leading to this confrontation. Much of what we can extrapolate – his affection for Mina, Kinnu, and Jay – seems contrary to his belief. If Jay believes, as he tells Mina, that they didn’t leave Uganda because of Amin and purely because of Okelo’s statement, doesn’t the very ground for their self-imposed exile stand on poorly displayed relations?

Ambition, possibly a filmmaker’s greatest asset, if left untested can pose more problems requiring answers. Airbrushing these problems can give you a postcard film – one that invokes momentary longing – but is ultimately too heavy to sustain. All these traces of rushed intentions to stitch together different societies would have been much better served if Nair’s original observation had given us a full film on diasporic crossroads down South. It would be a shame to lose Uganda, which had such promise at the break of its dawn, but it ultimately would veer the director much out of the comfort zone and the scaffolding she builds for the post-Confederacy states. You know how when you believe a heavy-handed spill of spice can give you the sublimity of two curries in one? Those hopes – both in the kitchen and at the writer’s desk – only meet dashed expectations and you’re left with a “mix masala” as Mina would call herself.