Grave of the Fireflies is a very unlikely marriage. Death, both physical and emotional, is a subject that is too literal-minded for the soft innuendos of animation in the 80s. The principal subject of any animation film is much preferred by the audience when she floats away on clouds. When she’s shown munching pebble-made rice balls, it’s unbearably leaden for them. Takahata was duly informed by his peers of the impossibility of his undertaking, and he still went ahead with an alliance between the two worlds. His tenacity to do so dragged Ghibli to the fore of world attention and he’s done it with such an unswerving incisiveness. Thirty-seven years on from when Grave of the Fireflies debuted to the world, it holds onto a tag that belies its categorical misplacement. For convenience, it’s a war film. But the real war is nested within it; a war fought by one soldier to shield the most precious of all human gifts – childhood’s innocence.

But before I can go any further, I’d like to clear up the unfortunate misinterpretation that shadows the film. It has been famously called an anti-war film. Superficially, there’s a lot that substantiates this claim; Takahata was affected directly by the bombings, and so was Akiyuki Nosaka, the author of the eponymous novel. Given the backdrop, one could call it a war film and I would acquiesce. If it wasn’t for my friend’s opinion, I would have perhaps not thought about how erroneous the anti-war tag that precedes the film is. For it to be an anti-war film, war needs to be indispensable in every circumstance that it creates. One could just as well replace the backdrop of war with famine, economic hardship, or plague and the circumstances wouldn’t change drastically. We don’t see Seita press-ganged into joining the war, nor do we see the delirium of battle. We only experience its knock-off effects – rationing, crudeness, and impartiality. You don’t need war to create that duress, any of the events that I’ve listed can do that for you. Come and See is an anti-war film because it speaks directly as to how Flyora is literally plucked from his idyllic village and placed into an impossible situation because of war. On the contrary, Grave of the Fireflies is a poem on innocence and sweetness being the first victims of any prolonged duress and how society collectively fails the most treasured facet of human development. Alex Dudok de Wit writes in his work on the film that “Yet it also belies the nuances of his (Takahata’s) intentions and indicates that, in an important sense, Fireflies was a failure” referring to the uniform response of critics and public alike. Though I’m unsure in what sense he means this, the tone he strikes with his remark is similar to mine; boxing Fireflies into the category of war pares off its universal potency.

Takahata’s notion itself was much more atavistic. His idea in relation to the source material was to interject a contemporary child of Seita’s age during the war. He’d felt that children during the war toed the line of obeisance without question, unlike Seita and Setsuko who are obstinate, akin to the unassuming children of post-war Japan. Perhaps, this is why he splits the final frame with the modernity of Tokyo vaunting its skyscrapers and progress against the children who were born too early to bask in its free-spirited indifference. But deeper than that, Takahata wished to dispel the inferiority complex, as he so calls it, that future generations develop when they see a film made about periods of hardship. When we see war films, there’s a sense of nobility, to our eyes, that compasses the populace; they negate desire, they stomach pangs of hunger, and they distance themselves from joy. But for many who have lived through it, they feel such an interpretation to be duplicitous. Nosaka himself has sworn off reading his work stating that he has depicted someone so removed from his years through the war. He’d felt hunger and he indulged himself, often at the expense of his sister. Takahata nods affirmatively to this notion, but he didn’t want to subvert the nobility, he wished to re-direct its pledge, staying true to the novel. Not to the nation nor to society, but to his sister. This path, the middle path, draws the contemporary audience closer to the subject, engendering a relatability to the characters while maintaining a form of courage that is still attainable and pertinent regardless of one’s misfortune. It’s to say that war’s unlikely heroes aren’t cut from finer fabric; they are, in effect, the children of today made to grow ten years in ten days.

Flipping through the interview archives, I’d found something that Nosaka talks about pensively that neither he nor Takahata choose to include in their respective works. But the vestiges of that idea, or rather that experience, are very pivotal to both the novella and the film itself. Takahata opens Grave of the Fireflies with Seita slumping against the pillars of Kobe’s station. The passers-by scorn these withering young men and the cleaners poke at them with their sticks as if they are dead mice. When war’s theater drew to a close in 45’, Nosaka had moved back into civilian life from the world of shadows. He’d done terrible deeds, but the moral palliative was always his sister’s betterment. With her gone and having sped through life, he was unsure of his comportment from that point onwards. Was he to behave like an adult or was he to regress and pull on the unsureness of boyhood? It was too burdening a question and the world wasn’t forthcoming with a solution. He’d since lived as an adult, and the unfortunate fatality was the years lost to the war and the years of boyhood left. Takahata opts not to show this choiceless transaction of years and lets Seita rest with Setsuko, facing away from the daunting bedlam of society’s new dawn.

In my earlier post about Princess Kaguya, I’d made mention of Takahata’s ability to diffuse a strain of emotion that reaches one’s core. While writing it, I knew that what I was mentioning was a very inchoate idea that had no expatiation. When Grave of the Fireflies did the same, there was a need to understand why this was happening. At Locarno, Ocelot and Takahata spoke about their careers and animation’s evolvement. Differentiating Western and Eastern perceptions of animation, Ocelot pointed out, in a moment of weighted brevity, a suitable cause for this phenomenon. Animation films are trojan horses, and this can work to an animator’s benefit if positioned correctly. In Japan, the tag of animation being a children’s pastime isn’t as prevalent as it is in the West. So, when an adult sits down to watch the film, there’s a sense of emotional disarmament in the absence of prior knowledge; the drawbridges are dropped, and you don’t see it blindsiding you with conflicting emotions.

Japan hasn’t always had the luxury of an all-ages audience for animation. Though Toei existed as a major animation house in the ’50s, Japan was renowned for its stable of live-action directors – Kurosawa, Ozu, and Mizoguchi led from the front. For Takahata himself, his inspirations came from outside animation during his years at Toei. So, leading up to Ghibli’s creation and the explosive reception of Anime as we know it today, there wasn’t much appreciation for explorative animation. The artist was, hence, whimsical. Japan’s animators made films, but the intention was to make it for themselves first before considering children. They were certainly conscious and mindful of who the film would reach, but that didn’t inhibit their pool of subjects. As Ocelot says, children don’t wish to be treated as children – there is an incipient adult within them that demands a patina of respect. Speak of what you wish to speak in a manner that doesn’t jolt a child’s developing senses while still being adequate to address themes for the court of adults. This precedent has since separated animation houses in the West from those in Japan. The animator’s liberty was expropriated by production houses who believed in tranching audiences. The result? A film that limits itself in both creation and appeal; it’s packaged for an intended consumer and therein it becomes a commodity.

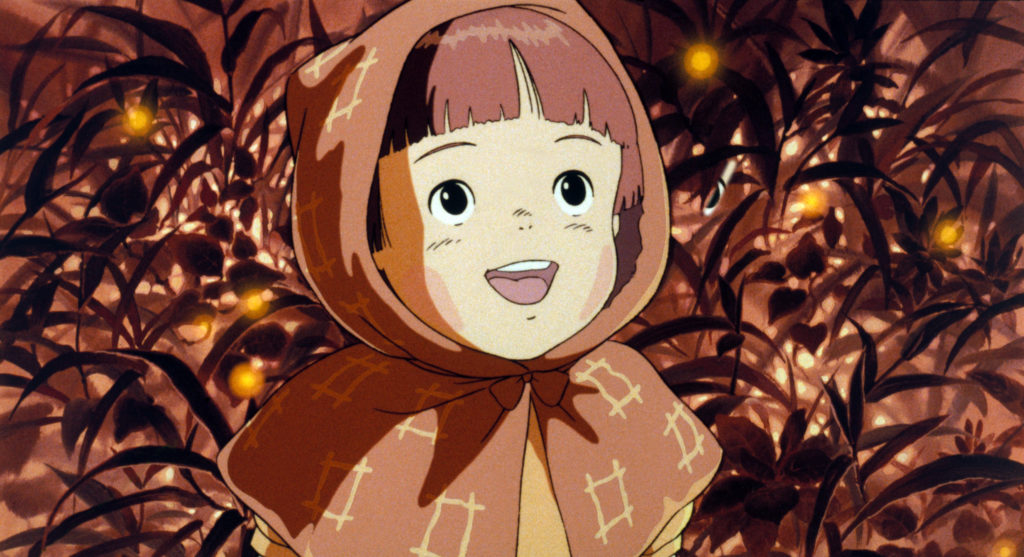

For all that it is, Grave of the Fireflies is timeless. Very few of today’s productions match its qualities and that isn’t solely attributable to the passage of time. When one looks at animations today, there’s a sheen of perfection in their textures and colors. In modern Anime, the characters are drawn crisply, and they seem ironed out. This isn’t to say that this aspect is a detractor, but an indication of how a creator’s tools have grown to become powerful. Ocelot mentions this as well when asked about 3D platforms; he remarks that when one works with limitations, one finds ways to overcome them. When the tool allows you limitless possibilities, you’re stuck in the hapless purgatory of a blank canvas. This isn’t true for animation alone. Look at live-action; handheld cameras have burgeoned, but the quality of films is yet to raise the bar. When working with limitations, you foster discipline and once it grows to become an asset, it helps you identify practices that can be inverted or subverted to achieve the desired result. For Takahata, this has always been a point of concern and despite the stage of his career, his opinion on imperfection has remained the same from Fireflies to Kaguya. The first product or rough traces always have more personality than the perfected sheets brought back after hours of review. What’s most striking in Fireflies is the softness of the images; none of the characters appear to be rigid apparitions. The animation team decided to employ brown instead of black for outlining characters and it lends a mild contrast against the landscape.

Above all, the line that delineates a removed viewing from an invested one is one’s own engagement with the characters, to the point of being rendered mute after the film. Takahata talks about this as well; when asked about Japan’s success in making animations that don’t limit themselves, he talks about distance and humor. Though he points out Spirited Away as an example of unnoticed humor, I’d take a leaf out of his own oeuvre. In Princess Kaguya, right before the final few moments, we see Kaguya’s handmaiden guarding her with a Naginata. A long stick with a small blade, it’s almost twice as big as herself. When the cut lands on her, you’d laugh momentarily before you stifle it; you’re invested in the story, and you find it inappropriate yourself. This investment in the characters’ draws heavily from faithful writing. But more specifically for animation, the perception that animators respect the audience’s maturity has helped Japan shirk the meant-for-kids image. On the other hand, the proofing and vetting that takes place in the West place a distance between the viewer and the film – you’d watch it from afar, you’d relate to the characters, and you’d laugh at the perfunctory jokes. However, at the end of the viewing, it’s more a parable adhering to archetypes; an overdose of preening and positioning to avoid being bold enough to challenge your preconceptions.

Between Miyazaki and Takahata, there has been a healthy balance. The former focuses on fantastic worlds, whereas the latter is a realist. Not a full-blooded realist, but still a realist. He describes himself as being more rooted in reality before moving into fantasy, whereas Miyazaki’s worlds are deeply intertwined to the point of indifference. Both began Ghibli’s fortunes with a double-bill – Fireflies and My Neighbour Totoro in 1988. They wished to mark Takahata’s end with a double bill, but his studious approach meant Kaguya was delayed. Both creators have been seminal in distinguishing Japanese animation in film, but Takahata has shouldered a larger risk appetite. Grave of the Fireflies did something unheard of and it ruptured the cage that animation was limited to since its inception.

It wasn’t easy to convince Nosaka to lend his novella’s children to the film world. He was adamant that the true devastation of the bombings can’t be captured through sets. He may have been right; one could have shown devastation, but it wouldn’t have been as ethereal as witnessed by its survivors. It would have been crude and brutal and there would be more disgust for the beholder rather than silent admiration for the pockets of beauty sought by Setsuko and Seita. In Japan, there was yet another taboo that animators can’t scout locations at home for reproduction. Takahata went out of his way to do so, and even rice paddies were never as lifelike to Nosaka’s eyes. The landscape needed that beauty; if there was nothing to admire, the loss wouldn’t feel as heavy as it does. Live-action will always be handicapped in this regard because one cannot manipulate reality. It brings me back to the point of Ocelot on animation being a trojan-horse; it’s convenient because one doesn’t expect to be overwhelmed with lowered drawbridges. But live-action and the immutable reality of its frame can serve the opposite purpose. When a director wishes to truly speak of brutality, as Klimov does in Come and See, you want the images to storm through one’s emotional dykes to reach the core.

Swathes of information and emotion, Grave of the Fireflies has been both edifying and deeply evocative. The flute and red hues that open and close the film are haunting because they walk the line between tragedy and peace. It will remain with me as more than a token reminder of the need to persevere. It’s been a long two years of plague and dissonance for many including myself, but the film’s core could not be clearer in its message – don’t be afraid to bite back at the martinet demons of duress. Don’t be afraid to preserve your humaneness, even if it means bending the new order of values.