With light stripping away half of the frame, surrendering the remainder to the shadows, all we see is a car surfing across Chinatown’s streets. Playfully deliberate, there’s even an everyday song that riffs an encore on suffocating inflation; we, just settling into our seats, would vaguely recognize its era by the distinct rhythm and instruments. But the language? Much like the man behind the wheel, that too seems unfamiliar at first. One could be forgiven, given the seeming American-ness, for surmising it as weirdly pronounced English without the aid of subtitles (which was how Chan is Missing was released during its original run in 1982). The final effect is a clouded mess – neither do we get to see the driver completely, nor understand the song that pulsates his car. By the end of the film, you realize that Wang has played on each frame with such fastidiousness (on a $22,000 budget, mind you) that the potency of his idea on lost identities reaches us lossless at every turn.

As all this unfolds, and the opening scene breaks onto a conversation that seems so unrehearsed, we realize that Wang has decided to go against mere realism and take a step further into the hyperreal. Despite it being a term that rarely features within the circle of cinema, his approach works much to fortify his driving question – what do diasporas feel concerning their home and adopted lands? We wouldn’t wish to engage seriously with this question should we feel in the slightest that it was merely a thought experiment, not one of genuine concern for the lived-in experiences of people in Chinatown. The chatter itself, though very characteristic of Chinese gatherings, reminds me much of Berlanga: rapid conversations that exhaust both the translator and the viewer. As in his multitude of films, here too you aren’t so much engaged in what is being conversed about rather than how. Wang wishes to capture a mode of speech, the way it reflects more about the interlocutor through delivery and frequency rather than content. He even teases, shortly after the premise has been established, through a paralegal on his conscious usage of the characters’ repartee. “Trying to relate possibly, or seemingly unrelated objects to the matter-at-hand,” she remarks about Chinese speakers, almost unaware that she is committing the same crime that she’s defending, as Jo and Steve watch on with the most puzzled of looks. It’s these small bolts of identity exposition that screw his core question onto the screen. All these scenes have a purpose, even ones that seem too smartly conceived to be real yet become commonplace when contextualized.

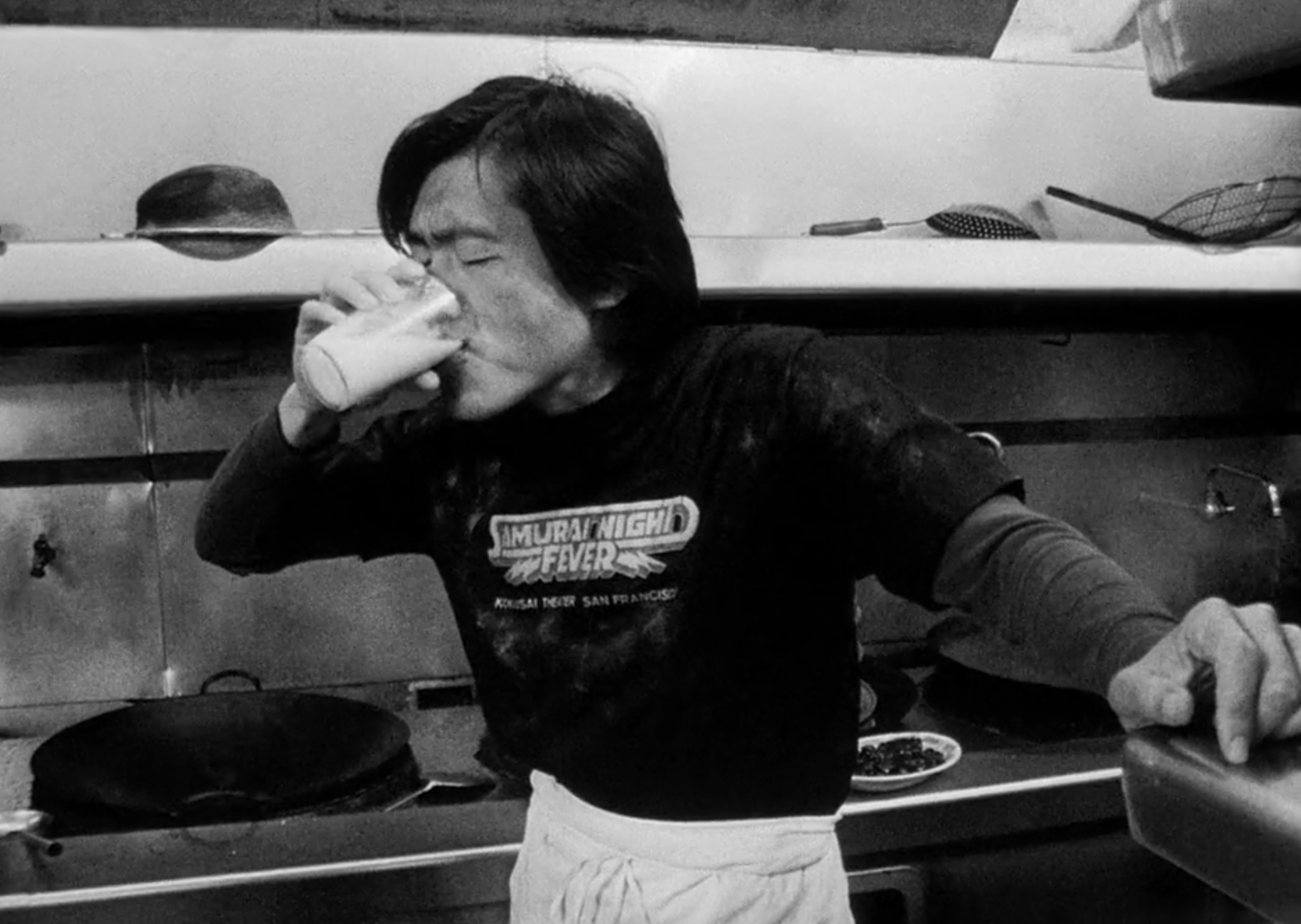

We see this reflected in his troop of characters, too. More often than not, we assume that the strands of flair assumed by characters on screen run counter to how people present themselves in reality. The idea that a person similar to a character could not exhibit those same mannerisms leads many directors to pursue a toned-down brand of realism. Nonetheless, in such (modern) films, I’ve always felt their constructions to be more stilted than their peculiar counterparts. There is this sense that, in a repeated interplay between art and reality, the people that we cross also organically imbibe shades of what they see. Wang, amongst a small crop of filmmakers, understands that as humans we tend to differentiate ourselves – sometimes aggressively, sometimes passively – to avoid losing ourselves within the larger community. Henry, the wok-whirling chef, is one of many examples in the film. Sporting a Samurai Night Fever t-shirt, tossing cheeky remarks at tourist orders, and questioning the suitability of kitchen work – all while washing his throat with a random glass of milk. Despite resembling a garbled back-of-the-envelope idea, he comes across as being extremely commonplace. It only affirms the notion that we construct ourselves using what circulates around us; in Henry’s case, and for most of Chinatown and modern society, it’s a mix of commodities, hot-selling ideas, and sterilized stardom. Wang’s origins in Hong Kong and his cinematic choices remind me of the early days of Wong Kar-Wai – As Tears Go By would release only 6 years later – and his focus on the birth of a new generation back home.

Having tabled the relationship between Wong Kar-Wai and his early American predecessor, I’m compelled to mention the similarities between their cinematographers – Christopher Doyle and Michael Chin. Though Doyle and Wong worked throughout their long, shared career to give us a sense of being the invasive spectator, Chin’s use of the camera is markedly different despite rendering a similar, observer effect. There are scenes, for instance, like that of the crowded Chinese restaurant. We feel pushed inwards, almost as if we are out-of-place participants, made to focus on what’s directly in front of us, not its peripheries. Characters of importance are always placed bordering the left or right thirds of a frame, almost as if they’re slipping away from our vision. The camera mimics the disorientation that an outsider would feel when entering these mini-worlds beneath or beside us. When they are in the centre of the frame, they are never allowed to fully occupy that space – light distorts them, or they are obfuscated by their retinue. Largely hand-held, the film follows this pattern of instability except when Jo or Steve find themselves in a moment that puts their identity in question. These choices are unique; they neither follow the urgency of a documentary nor the pristine imagery of Hollywood. Unintended? Wang is too shrewd, nor am I that harsh in my appraisal. His film has traces of self-awareness and deserves the benefit of the doubt.

Chan is Missing, since its release, has not got widespread recognition over the years. Scale and its side-stream origins ensure that it has remained so, but I feel the film to be pertinent to much of what modern cinema is trying to be but fails to achieve. Wang has fashioned a film that understands the nuances of identity and doesn’t force these to be loud and imposing. Though he was aware of the pressing need to tell the story of Chinatown through its own members, he didn’t place it as his sole priority. The film was to be a thought experiment, deriving from the form-breaking efforts of Godard, a modest plan of action based on Eisenstein’s theory on the Chinese language’s similarity to the modern montage. The final product, regardless, differs from this radical beginning but maintains the principle of basted scenes accentuated by dialogue and voice-overs. Hence, with this focus on presenting his subject as-is with modifications in form, he manages to achieve a film that is truthful to its people and its audience. Unsurprisingly, Wang was an outsider and arrived in America at the muddling age of eighteen with no preconceived notions about the opposing factions of Chinatown. This neutrality is much harder to possess for those who set out to document stories of their land, yet those who achieve it often render their cultures a service far greater than a fiercely coloured presentation.

As a final feather in its cap, Chan is Missing achieves what other films struggle to knot into their narratives – an open-ended conclusion that segues naturally from the progression of events. “The problem with me is that I believe what I see and hear,” laments Jo as he rolls back into Chinatown on his Wing On Cab. His statement is consistent with the viewing experience we have by peeking over his shoulder, watching a world where people are both confirmatory and contradictory to our pre-wired notions of them. We hear much of these people, we see them momentarily, and listen to their opinions, yet we can’t fully place them under a stamp. With its men described as a genius by some and toddlers by others, Chinatown is much like any community that has fenced itself in while leaving the gate ajar. A melting pot, yes, but Wang doesn’t wish to praise this overflow of cultures. He asks us to engage with the dissonance of their days and their quiet acceptance of it.