A rusted nail is driven through a stiff palm. A coffin that belies the jester that lies inside it. The whirring of a tape that doesn’t anticipate the fire which will soon engulf it. A spider whose eyes are blighted by a lamp that is too close. A boy who caresses the cellular apparition of a woman, or two. A man who immolates himself, unaware that his flames are being broadcasted to frightful effects.

This is Persona. Sensations abound before thought can place together bricks to make sense. It’s a viewing experience that has flabbergasted all those who have sat down to watch it, and it left me in quite the same state. Many have, in critical circles, called it the Everest of film criticism. I feel that there is not much to critique. You only divine from this film, as one does from the multitude of experiences that one encounters. Water may crash against rocks, flowers may stay the onset of Spring – for some they remain mundane, for some they remain profound. Persona, for what it is, is quite similar. Bergman is so obstinately against form and structure, so much so, that you have to ask yourself – is this still Cinema? It’s almost as if you stitch together the torrent of thoughts that may exist in your mind surrounding femininity, marital relations, identity, and character only to condense it as a jolt of beauty and terror.

It’s been roughly 2 days since I watched it, and it reminds me terribly of Tarkovsky’s Mirror. But to his credit, he outlines quite patently the bounds of his exposition. Mirror talks to us about the yearnings and tribulations of a dying Russian poet. Within those bounds, you could see that the images that floated through the screen were probably an amalgam of all the tender, frightful, and seminal moments that a man might envision on his deathbed. Here, there are quite frankly no bounds. We know nothing about Alma and Elisabet, the two principal conduits. I call them conduits because their pasts don’t move the film towards any resolution, nor do they themselves complete an arc during its course. Their moral compasses are not pre-established, and we can never really pin down traits or attributes to them. Perhaps, the only attribute that is overt is Alma’s verbosity and Elisabet’s obstinacy – which too wanes with time. They exhibit their creator’s emotions without adulteration.

Any viewer unfamiliar with Bergman might call this a mental barf and be off with it. But, I’ve seen Fanny and Alexander, a film with many structural contours that explores so much. So to see Persona is quite shocking. On one hand, one must admire the ferocious commitment to be against interpretation – he has produced a film worthy of that commitment. But it isn’t drivel because it contains moments of cinematic brilliance. But to highlight those, I should provide whatever context does exist within Bergman’s creation.

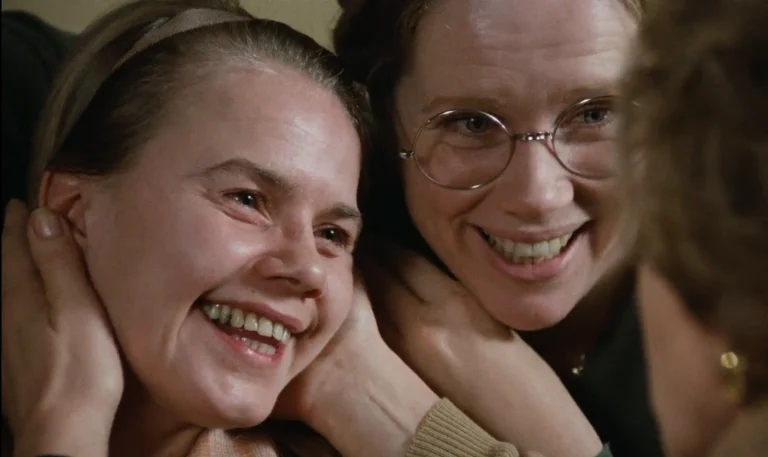

Persona’s world is sparsely populated. Alma and Elisabet are its primary inhabitants, and we follow them from their first meeting at an unnamed hospital. Alma has been assigned to Elisabet – a patient in one of the wards. Elisabet is healthy, both mentally and physically. An actress by trade, she stops in the middle of a theatrical rendition to take an oath of silence. Effectively, the only thing she suffers from is unyielding willpower, according to the chief doctor. Since her condition doesn’t warrant her stay there, she is soon sent to a summer house alongside the coast, with Alma to accompany her. Herein, they reflect off of each other and tear their personas down to the point of dissolution.

Funnily, the woman who wrote Against Interpretation is the one who has probably furnished the strongest of interpretations for this haunting cacophony. Sontag wrote in Sight and Sound, and here’s an extract from that, which would encapsulate this cacophony with words that I can’t conjure at the moment –

Violence and the sense of horror and impotence are, more truly, the residual experiences of consciousness subjected to an ordeal. It isn’t that Bergman is pessimistic about the human situation – as if it were a question of certain opinions. It’s that the quality of his sensibility has only one true subject: the depths in which consciousness drowns. If the maintenance of personality requires the safeguarding of the integrity of masks, and the truth about a person is always the cracking of the mask, then the truth about life as a whole is the shattering of the total façade behind which lies absolute cruelty.

I’d like to focus exclusively on the part about the maintenance of personalities because I believe that’s the part that spoke to me the most throughout the film. Elisabet has already avowed silence and believes that to speak is to belie the actual human condition. Her trade has made her wear many masks, and she feels fatigued by these masks. So her oath is to shatter the mask through unrelenting silence. So, as Sontag surmises, she then assumes the natural state of being cruel. By interdicting herself, she has self-inflicted violence upon her mind to not express and will inflict the pain of assumption on other minds that brush against hers.

Alma, however, is unpolluted. She is still endeared to her masks – being a good wife and being optimistic about the years to come are foremost of those. She pours out extracts of her life to Elisabet. Bibi Andersson as Alma is fantastic in her squirming confession of an orgy she had never intended and a child she didn’t wish to abort. But realizing that she’s merely a curious study for Elisabet, her verbosity reduces, and we begin to see her shed her masks as well. She decides to inflict the cruelty of assumption against Elisabet and the film moves into further abstraction. It’s almost as if Bergman is trying to locate sensations and ideas and sever them firmly from these characters.

The film houses many more themes, but I feel further dissection is futile. Let it allow you to sense it. It’s amongst Cinema’s grandest efforts to isolate thought and ideation from the clutches of our tendency to associate them with one particular man or woman. He wishes for us to see them in their truest state, which is an impossible feat as long as one is within bodily confines. The effort towards this direction is, nonetheless, stupendous.

Earlier, I’d posed a question rhetorically, yet still, I’ll bring it back once more – Is this still Cinema? The conventional norm is that Cinema is logically constructed. Its bounds are explicit, regardless of what it wishes to show. But Bergman has transcended that and has presented something that pushes those bounds into non-existence. It’s one of those few times when I’d sensed a lot in flashes and nothing at the end. It is a reflection of the state of my mind without the logical progression of curation and construction. Perhaps, I would one day like to film something similar, but I’m too unsure if I’d be as open as Bergman in wanting to display it to the world.